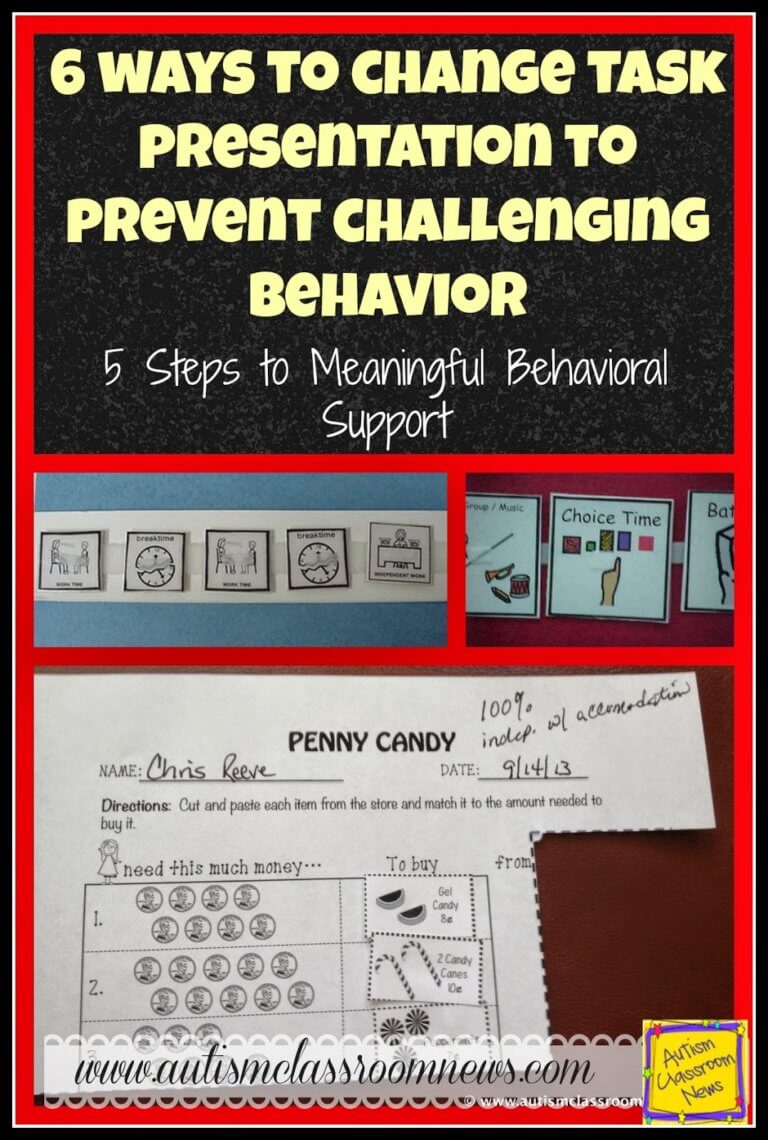

To check out the rest of this series on 5 Steps to Meaningful Behavioral Support, click HERE.

If this series proves nothing else, it is that addressing and preventing challenging behavior is a complex, complicated, long job…and it is. But there are some things you can do that will prevent challenging behaviors just in the way you present tasks to students. These will work well if you have a student whose FBA showed that the behavior served to escape from demands from staff or parents. Essentially these are strategies that will lessen the student’s negative response to task demands by making them easier, more interesting, and/or more palatable in some way so they are more likely to comply. And let’s face it, increased compliance, and decreased challenging behavior is a win-win for you and the student. So, let’s look at some strategies.

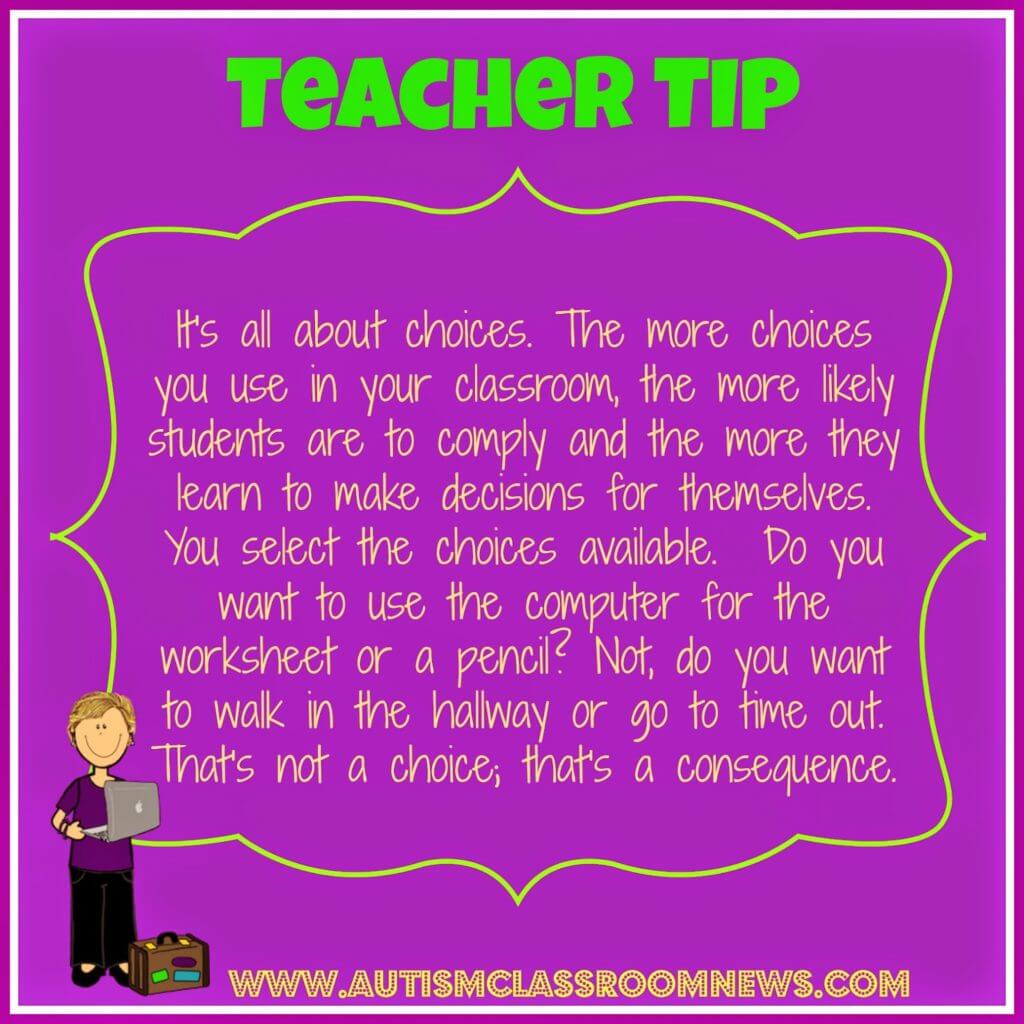

1. Give choices

Present the task demand with a choice built into it. For instance, if you want Jim to do a math worksheet, you might ask him if he wants to do the math worksheet from the beginning to end or from the end to the beginning. Or you might ask him if he wants to do it with a pencil or pen or if he wants to do it at your desk or his desk. We have some good research that giving choices in demands decreases challenging behavior (Dunlap & Kern, 1996). However, it’s important to remember that choices are not between undesired and desired activities. So you wouldn’t give a choice of “Do you want to do your math or do you want to go to Disney World?” Clearly in this choice you wouldn’t get YOUR choice, which is for Jim to do his work. Similarly, choices would not be a consequence.

You wouldn’t give a choice of “Do you want to do your math or go to time-out?” If time-out is undesired (remember sometimes it isn’t the punishment we think it is), then this is a threat, not a choice. The point of choices is to give the individual some level of control over the way things get done while still following through. Once someone chooses something they are more likely to follow through and it allows them to “save face” because they get to have some say in what is getting done. Here are some tips for using choices:

- Choices should include 2 or 3 choices of things that you can provide, that still get your goal met.

- Present choices either verbally or visually depending on the comprehension level of the individual.

- Make a list of choices that can be easily offered by adults and post them around the room for easy reference. It’s not always easy to remember what types of choices you can give.

- Mix them up and be creative.

2. Present Directions Positively

Consider presenting tasks in a positive way that kind of lays down a challenge or that assures the individual they can do it. For instance, instead of saying, “It’s time to do your math.” You might tell Jim, “You are such a superstar in math. I can’t wait to see how you knock this worksheet out of the park!”

For students who are competitive, you might suggest a race. For instance, “Do you think you can finish your work before I finish mine?” Or, “I bet you can get this whole set of tasks done before lunch time!” or for some students you might lay down the challenge by saying, “I don’t think you can get this whole set of work done before lunch! Prove me wrong!” Just be careful with that last one. If you are working with an anxious student, that is likely to make them take your statement at face value and not as the challenge you intended. Then it will become a self-fulfilling prophecy because he will believe he can’t do it.

I’ve been using this strategy of telling students how super I know they can do with the task more and more recently and I’ve been amazed how many students will try things they might have rejected otherwise.

3. Pacing

The way you pace your instruction makes a difference. Downtime is not your friend in any part of the classroom, and research has shown that increasing the pace of instruction (presenting tasks more quickly with less time between them) typically improves compliance (Dunlap & Kern, 1996). For instance, if you are using a discrete trial approach, mixing up the tasks and presenting them in quick succession with only seconds in between them increases completion whereas having to wait between tasks presents the opportunity for more off-task behavior.

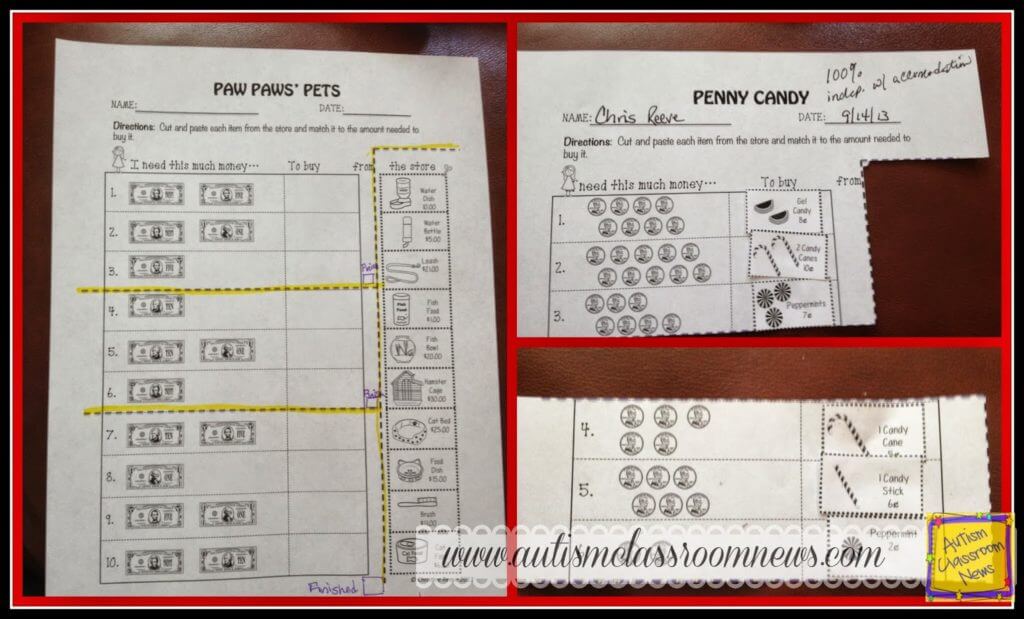

4. Present Smaller Amounts

I talked about how to adapt worksheets for this strategy (and there is a freebie) in this post. Sometimes presenting the whole task is completely overwhelming to our students (and to us). Imagine that you are in a graduate program and someone gave you a syllabus for every class you had to take to get your doctorate and you had to start at the beginning and get to the end. I know that would have overwhelmed me and I likely would have given up. We don’t do that in graduate school and we shouldn’t do it at a lower level to our students. Sometimes seeing the whole picture is just too much.

We have used modifying the amounts of work as an accommodation for students for eons, but we sometimes forget that with the difficulty our kids with ASD have in noting the big picture versus the details, that we need to break the task down VISUALLY, not just telling them to do less or do smaller chunks, in order to prevent them from panicking.

5. Behavioral momentum

Behavioral momentum is a behavioral principle that essentially indicates that presenting a number of high probability tasks (i.e., easy, mastered material) before presenting a low probability task (i.e., harder work at their learning level), individuals are more likely to follow through with the low probability task because the momentum carries them through.

So what does this mean in your classroom? It can be used in two ways. You can organize your work time so that it has high levels of easy (high probability) tasks in contrast to the difficult (low probability) tasks. In short, embed your grade level or challenging material into a set of tasks that are easy.

So, I have a student I work with who is really challenged by anything involving language (not unusual, I know). However, his challenges manifest themselves in him hitting and throwing when presented with speech activities and reading comprehension. So, to help him be more likely to answer the “wh” reading comprehension questions, for instance, we do lots of matching and rote identification of pictures from the books and then throw in a “wh” question about when or where something in the story occurred. When we preface that comprehension question with lots of matching and visual tasks, he is more likely to answer the comprehension question without throwing materials or hitting staff. Work may seem to go slower, but since we don’t have as many work stoppages to deal with challenging behavior, it actually progresses faster.

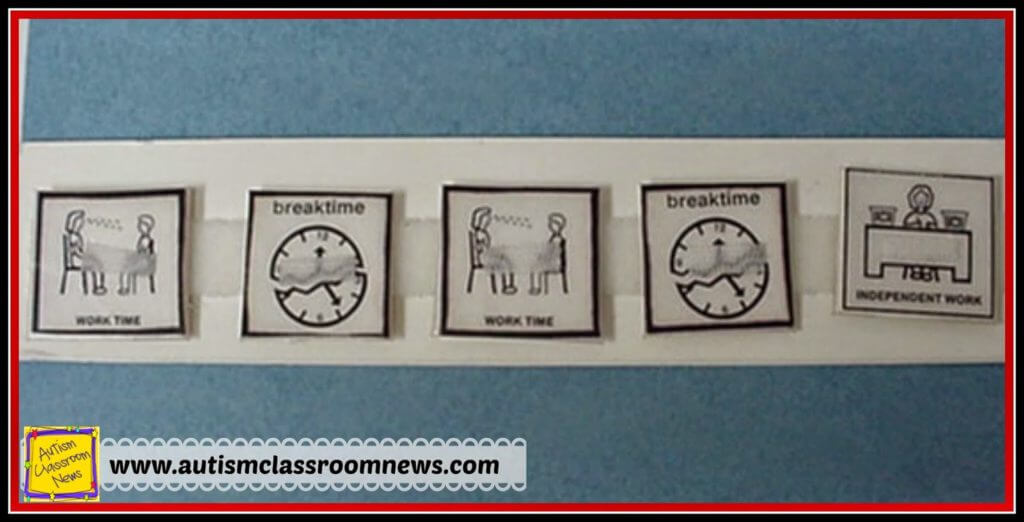

6. Use Work-Break routines

One way that changes the way we actually schedule for some students is to present tasks in a work-break format. We might do 10 minutes of work followed by 5 minutes of break throughout the day. These are students whose challenging behavior is significant and who are not able to work for longer than the work time we assign without challenging behavior. We then use their visual schedule to show them how the work will be scheduled, like the work-break schedule you see below. This helps reduce challenging behavior because they can see a short period of work will be followed by a non-demanding activity of a break. We often use a timer to let the student see how long he/she is expected to work which lessens the aversiveness of what we are asking.

So those are just some of the ways that you can modify the way tasks are presented to get better compliance and prevent challenging behavior for students whose behavior functions to escape from demands. For a great review of curricular variables that affect challenging behavior, check out:

Dunlap, G., & Kern, L. (1996). Modifying instructional activities to promote desirable behavior: A conceptual and practical framework. School Psychology Quarterly, 11(4), 297–312.

What have you found works to prevent challenging behavior in the way you present tasks?

Until next time,