Wow, I am currently at the OCALI Conference in Columbus, OH and it’s a good thing I own warm clothes! I don’t know how you northerners do it!! It’s freezing here! Today, Susan Kabot and I presented to a great group on strategies and resources for making sense of all the information that is out there about autism. Just trying to keep up is more than a full-time job with new “scientific” information coming out every minute and everyone claiming to be a scientifically based program. I had mentioned the talk on Facebook and said I would share the handout here after the presentation. If you attended the presentation and want to download the handout, just zip to the bottom of the page where I’ve placed the link. If you weren’t able to attend, let me share just a couple of thoughts about the topic so that the handout will be understandable.

I’ve discussed evidence-based interventions in the past and some processes for evaluating interventions in previous posts HERE. I don’t want to repeat all of that but I do want to add some thoughts that resulted in this particular talk. I’m sure many of you have the experience of many people, from students’ parents, to administrators, to your own family who share newspaper and magazine articles and websites about the next great intervention for autism. There is so much information out there that it’s very difficult to know what you can trust. The presentation we did talked about the way we, as human beings, process information and make decisions and different decision models that we make. As educators and other related professionals, we have an obligation to make decisions about interventions based on research that has shown them to be effective. We then have a continuing obligation to determine if those evidence-based practices are appropriate and effective for our clients and students by evaluating the data produced when we apply them.

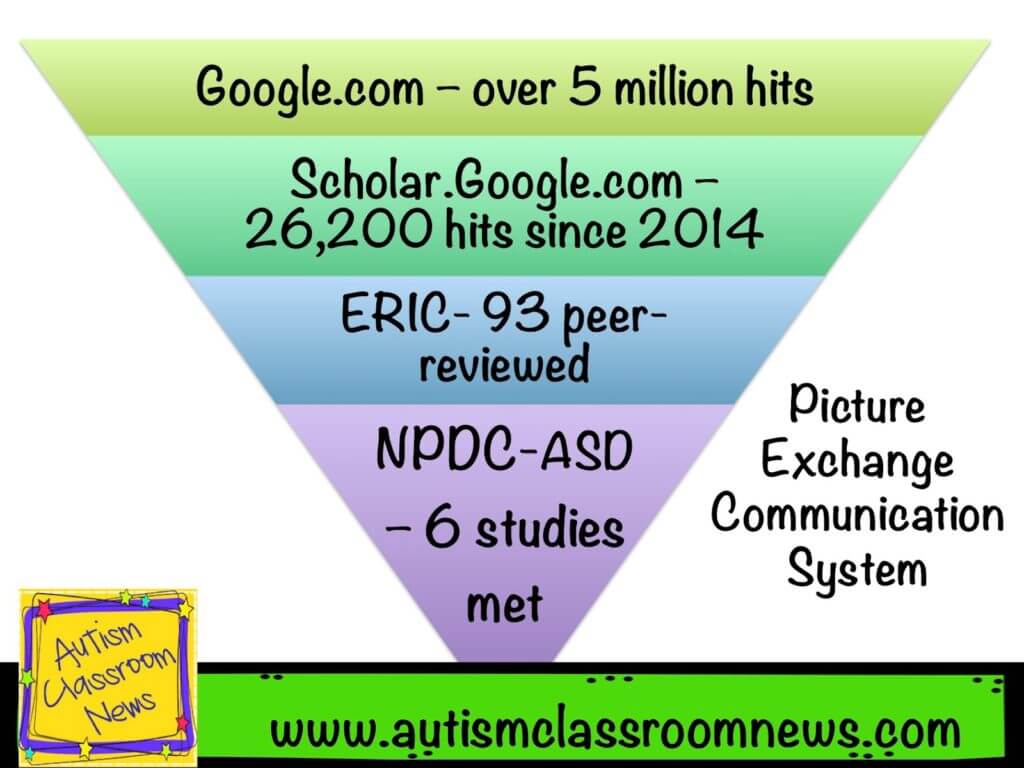

|

| Information gained from different channels when using the search term Picture Exchange Communication System |

Typically, most people operate on an expert or perceived expert-based model. If I’m sick and go to the doctor, I don’t do a literature search for every single piece of advice she gives me; I rely on her expertise. If I did a literature search and evaluation for every piece of advice I’d make myself crazy (which would require more internet searches to address that) and I would be exhausted. In addition, I would probably find a million reasons why I should do her suggestions and a million opposing reasons as well–and who would I believe. Believing experts is just less taxing. The graphic at the left is a great example of the number of hits you get when searching for information on PECS ending with the smallest number actually being considered good enough to make up the evidence base of the intervention.

However, as educators, YOU are the experts. The parents are the experts in knowing their child and what works for him or her. You, as an educational team, have (or should have) expertise about what the research says about how to teach students to read, how to reduce problem behavior, etc. That’s why understanding evidence-based practice is so important for educators.

Sometimes we operate on a expert model where we misperceive who the expert is. I think of this as the Jenny McCarthy model. A celebrity or a well-known advocate or person says something is effective and it gains favor because people associate them with the product. This is not research-based information and is often something to be suspect of. Testimonials are similar. Often times companies will gather testimonials about their intervention to sell them. This also isn’t research; it’s personal experience.

Similarly when you go a website to find information about an intervention, you often find a tab called “research” or “evidence base.” Don’t assume that what is in that part of the website is research. Many times I click that tab and it says Coming Soon or I find testimonials. Sometimes I find research, but it’s research that has been done only by the company trying to sell me the product. Or I find information about the product and how it’s been used all over the world or anecdotal (75% of the students in xx land made significant gains using this intervention). None of that is research and it’s information that we all want to be cautious about.

So, in order to determine what constitutes a practice worth investigating we need to focus on the research literature. To do that you have to have some understanding of the research literature. However, again, having to painfully search for every little piece of information you need to do your job is not possible with all your other duties. There are some resources, like the National Professional Development Center that are designed specifically to help you find the research behind information.

After we find the intervention we want to try, we have to be sure we have clearly defined what we expect it to do for our student and what the outcomes are we expect. We have to make sure that we implement the intervention the same way it is intended (with fidelity) in order for it to remain evidence based. A poorly executed evidence-based practice is no longer evidence based.

After we find the intervention we want to try, we have to be sure we have clearly defined what we expect it to do for our student and what the outcomes are we expect. We have to make sure that we implement the intervention the same way it is intended (with fidelity) in order for it to remain evidence based. A poorly executed evidence-based practice is no longer evidence based.

Then we need to measure them to find out if this approach works for this student. Every evidence-based practice is not effective for every student. We have to monitor our outcomes and see if it’s a good fit for the setting and the student based on those outcomes.

So that gives you some idea of what the presentation was about. You can download the handout HERE and share any questions or experiences in the comments. In the handout are links to useful resources about evidence-based practice you might find helpful.

Until next time,