Welcome to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast, the podcast for special educators who are looking for personal and professional development.

Christine Reeve: I’m your host, Dr. Christine Reeve. For more than 20 years, I’ve worn lots of hats in special education but my real love is helping special educators like you. This podcast will give you tips and ways to implement research based practices in a practical way in your classroom, to make your job easier and more effective.

Welcome back to the Autism Classroom Resources podcast. I am Chris Reeve and I am your host. And I am so glad you’re joining me today because I am going to talk about instructional strategies and some of the myths behind them and how they fit into the CORE model.

To be upfront, I’m going to talk about how good instruction of any kind often has the same components. Did you know that the same strategies that we use to train staff are parallel to the ways that we effectively teach our students.

The world of autism specific interventions would often have you think that there’s only one model of instruction that would work, everybody will tell you, you know, oh, you have to use this strategy, or you have to use that strategy. It’s not always the same strategy. Or maybe there’s a menu of strategies, but they all have to be from one specific discipline.

Sometimes the person making the argument is talking about Applied Behavior Analysis, and is putting it out there as the only discipline that should be used. Sometimes it’s an Early Childhood Professional making the argument that all young children even those with autism should be taught in a play based model, because developmentally, that’s age appropriate.

But today, I’m going to talk about why those two people and numerous others who want to sell one thing, may not be talking about things that are as different as they seem. And I’m going to be busting some myths about instruction, particularly in the world of ASD. But again, I think they also apply to some of our special ed students. So let’s get started.

My background is in psychology, and more specifically in cognitive behavioral psychology. My dissertation focused on how to prevent challenging behaviors from escalating in children with disabilities who had minor developmentally appropriate behavior problems. Think tantruming for a two year old. Appropriate for two year old, not for an eight year old. My focus wasn’t how to keep these situations from making the behaviors worse in common instructional situations where a teacher might be working with this student and a peer, and maybe the peer doesn’t have a lot of behavioral issues.

Now, my dissertation is grounded in the work of ABA. I am a behavior analyst by trade. My advisor was an ABA behavior analyst, so I’ll talk about him in a minute. But my dissertation was also grounded in the work of countless speech language pathologists, and educators, and psychologists. And I was lucky because when I was completing my literature review, my advisor sent me to the library to look up Barry Prizant’s work. Dr. Prizant is the SLP, who developed the SCERTS model. And he’s best known for some of his research on echolalia and communication temptations to get initiation of communication.

And my advisor also sent me to look at other SLPs work, as well. Some of the earliest research on new uses of symbols and pictures, because I’m old, and I did my dissertation a long time ago, was Lyle Lloyd. And so I read a lot of that. My point is just that my advisor did not limit me to just literature on the ABA. He didn’t say I only want to see articles in The Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. That’s because he was Ted Carr. And while he was a behavior analyst by trade, he was a scientist, above all, and science should never be developed in a vacuum.

Developing scientific theories in a vacuum leads to bad science, because you exclude all the confirming or refuting information that’s out there. It’s easy in science to see what you want to see. Even in the best controlled experiments that rely on observation. It’s easy to see what you’re expecting.

I once heard Laura Schreiben talk an amazing researcher in the world of autism. And she commented on the fact that the her results of her study did not turn out the way she expected. And it was a real testament to what the scientific process can do. Needless to say, I learned a ton from Ted as my advisor, and not just in how to do research or the psychology content that he taught me or the ABA.

I learned from his model and how he brought us up for better lack of a better term, the way he raised us, that it’s okay to disagree about science and what it means. But you have to be prepared to back up your argument. And you have to base your argument on science.

It’s okay for other people to disagree with your view as well. Just ask them why. And interpret it that way. And amazingly, you might learn something. Those kinds of professional discussions were a huge part of what Ted imparted to his graduate students. By now, you’re probably wondering why I’m telling you this very long story about my past background. And it’s partly because I think it helps you to know where I’m coming from.

But I also think it’s helpful to recognize that it’s a big world out there in the realm of science. Education, needs to be a science, we need to know what we’re doing. We use evidence based practices, that’s science. It is an art in how you make it all come together, and how you figure it out. You know, interpreting data is something of an art as well, it is a learned skill, it is a practice skill, and there are scientific principles. But how we put this all together is definitely something of an art in the way that we do that.

But in your discipline, whether it’s counseling, speech, education, ABA, psychology, your discipline is not the only one that’s doing research to find out how things work. But mostly, I’m telling you this because it relates to the main topic of today’s episode, which are myths about instructional strategies in special education. I did not forget what I was talking about. So let’s get started.

In last week’s episode, in Episode 168, I talked about the importance in the CORE model of making decisions based on the individual student. There is no one size fits all educational model, or instructional strategy in special education. Those of you who have been special ed teachers for awhile get that, because you’ve probably realized already, that you have to be the expert in everything when you have such a diverse classroom.

You have to learn about teaching students with visual impairment and students who are in wheelchairs and have physical needs for movement and positioning. being an augmentative communication specialist, and all different kinds of things, not to mention, a reading and math specialists. And on top of that, you need to be the instructional expert on the team for your students. And it’s a lot I know.

But I had good news, you can do instruction in a ton of different ways across the classroom. In the same way that you might do a combination of small group instruction and large group instruction, you can use specific teaching strategies based on the skills and on the needs of your individual students. And in fact, that really is what we should be doing.

But there are some elements that are going to be the same across quote unquote, different kinds of instruction. And those elements are what make it all work. Ron Leaf is a behavior analyst who worked in the early intervention, low vos studies and goes on to talk a lot and write a lot about Discrete trials. He used to say, I assume he probably still does, good teaching is good teaching. And he’s right. Good teaching is good teaching.

I have sat next to teachers who are doing discrete trial training, but have no idea what that term means. I had one actually say to me, I need you to teach me this. And I’m sitting there watching her differentiate Discrete trials across three different students and do it beautifully, and I’m thinking, you already know how to do that. I just have to name the things for you so you understand when other people are using that jargon in that language.

When you spend a lot of time like I do, observing different kinds of instruction, you find that they look a lot more similar than they do different. That’s the reason why the strategy you use to entice communication from your students in your classroom as a special educator, often look very like the same strategy that the SLP is using in their therapy room. You may call it one thing, your behavior analyst may call it another. You may call it incidental teaching. And the speech therapists might call it milieu training. Different names, but a lot of the same components.

So let me get to some of the myths. One of the instructional strategies that is frequently recommended for children with autism is applied behavior analysis and typically, specifically discrete trial training. Discrete trial training involves setting up situations where you are giving a direction, you’re waiting for a response, you’re providing some sort of prompt if it’s needed, and then if it’s correct, you’re going to reinforce it. And if it was incorrect, we might do an error correction procedure. Or we might just pick up the materials and move on if we’re using errorless teaching.

What’s really interesting about that is that this cycle looks a lot like other cycles of instruction. If I’m doing incidental teaching, which is another behavior analytic strategy, then I’m creating a situation. The difference is, I’m not telling him what to do, I’m sabotaging his environment. So the environment is setting the stage for this skill.

So the student needs to make a request or label something, or whatever the skill is, and what I’m working on and when that is complete, then I’m either reinforcing it, if it was correct, giving an error correction procedure, if it wasn’t, or picking it up and moving on, depending on how I am handling errors.

So one of the myths in autism is that all children have to have intensive discrete trial training. And that’s a myth because it doesn’t actually work for every child on the spectrum. In fact, our Early Intervention literature finds approximately a third of young children in early intervention, given intensive Discrete trials, like up to 40 hours a week, don’t make the significant gains that everybody says that they see with the other kids.

Now, the other third might may have made amazing gains, and another third, maybe making moderate gains. But there’s a group of kids that we still aren’t reaching, even though we have so much information about how to implement how to work with children with autism now than we used to.

What is the outcome of that research was that many people abandoned a lot of other strategies that we know to be evidence based, and research based, and have a lot of information that we can use. And that means that a lot of teaching strategies that might have reached some of those students who weren’t being reached, weren’t being tried.

It also really emphasizes the fact that we need to base our instructional decisions on what the student responds to. Now, I’ve been in many situations where the child was in, say, a play based developmental program. And he wasn’t getting enough opportunities to practice the skill, he wasn’t getting a real consistent presentation. And he wasn’t making the progress that the typical kids were making.

But I’ve also been in a situation where students are getting intensive, discrete trial. And they’re not making the type of progress that you would expect. But in their naturalistic instruction that is embedded into the areas of the classroom, the things that involve going and getting my lunch and setting it up on the table, or being able to take off my jacket and put it away, my arrival departure routine. The things that are embedded into the naturalistic instruction areas, those things that student might have been making progress on. And what that data tells me is, I need to shift his instruction to be more naturalistic, because the discrete trial is not working for him. Because that’s not what the data shows.

I was listening to a talk by Dr. Irene Schwartz the other day, and she’s a behavior analyst who works in early intervention, and she’s extremely practical. She’s very down to earth, she’s very easy to understand, if you ever had the chance to listen to one of her talks, she’s definitely worth it. And she had a really good description of good instruction.

She called it an instructional loop that we are setting up and initiating that instructional loop. So in our discrete trials we’re giving a direction and incidental teaching, I’m setting up a situation. I’m presenting them with a problem. If I’m using communication temptations where I wind up a wind up toy, and then it winds down and the student has to do something to get me to wind it back up again. That’s sabotaging that situation.

So essentially, in both of those, we’re setting the student up to need to use a skill, whether it’s because we tell him to do it, or the situation demands it. So we’re creating a situation in which he needs to do something. And she emphasized the importance of these loops, that the loop is you’re giving that direction, you’re waiting for a response. You’re giving prompts, if it’s part of your program and what the child needs. And then you’re either reinforcing it or not reinforcing it. Which that last piece is what she calls closing the loops.

And she talks about how important that is because we see lots of people give instructions. Lots of people give instruction. They may even prompt to get the student to do it. But a lot of times the piece that gets missed is closing that loop. It’s getting that reinforcement, it’s getting that feedback that that wasn’t the right thing.

So the important piece is that we have the elements that actually lead to learning in our loops. So we’re setting up a situation with the direction or the environment in a way that’s clear to this child. We’re anticipating and waiting for a response from them. We’re using some kind of systematic prompting strategies that we can fade out over time. And then we’re closing the loop by reinforcing a correct response, or giving an error correction, or just picking up the materials if we’re using an error loss learning strategy. That’s the loop closing. The loop is that piece that we often forget.

So interesting, and another thing that I really wanted to focus on today is that these loops that Dr. Schwartz talked about are prevalent in a lot of different kinds of instruction. They’re in Discrete trials, Discrete trials is probably the most concrete version of those.

I think she made the comment that if you can do Discrete trials, you are going to have a better chance of doing effective naturalistic instruction. But if you can’t get that loop in a really tight way, creating those opportunities in natural environments gonna be much harder. And I think she’s probably right. It’s a whole lot easier for me to train people to do Discrete trials, than it is for me to train them to do naturalistic instruction, because there’s a lot of different elements that make that harder.

So the but that same loop is in incidental teaching. Those same loops are in pivotal response training. Pivotal response training is kind of a blend of Discrete trials and naturalistic instruction. We have research now. And slowly, we’re getting people to recognize that the research exists, that naturalistic instructions can be as effective in early intervention as Discrete trials, and ABA. But I think that we’ve been a little slow to adopt that. Because it’s easy to get stuck on those early answers. There’s a lot of research reasons behind that. If you want to have a conversation with it email, email me, and I’ll be happy to share my thoughts on that.

So you can go outside the world of ABA. And when we look at good speech therapy, good speech therapy has the same loops. I talked about Dr. Prizant earlier, and communication temptations. Communication temptations are when you’re setting up a situation in which the child is tempted to communicate. I blew the bubbles, I put the top back on the bubbles, and he wants more bubbles. So now he has to give me the jar, or he has to point or he has to gesture, or he has to give me a picture, or he has to say bubbles, or give me some sort of verbal approximation. Whatever the skill is, he has to do something, I’m going to shape it into what I want to see in the long term using my closure of that loop.

So interestingly, if we even go outside the special ed world, and we look at an Anita Archer, and Anita Archer calls good instruction, explicit instruction. And I think that really describes a lot what a lot of our students with special ed need, they need explicit instruction. They need us to be very clear in our instruction. She’s not teaching students with autism, she’s typically teaching reading or other academic subjects to students, maybe with you know, similar strategies, she bottles those strategies that can be used in the classroom. But she’s using that same loop, it just looks a little bit different in her gen ed classroom.

She’s advocating for that same intensity of instruction, that same loop repetition, they’re getting lots of practice of a skill, by being directly taught the skill. Not just giving a lecture or throwing something out there and seeing if it sticks.

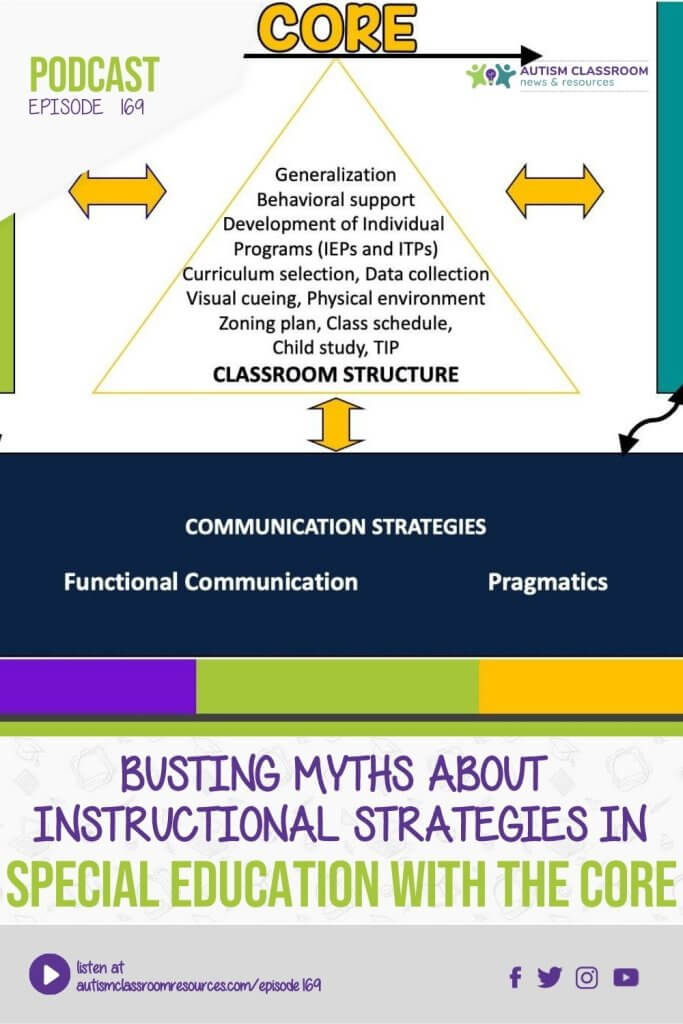

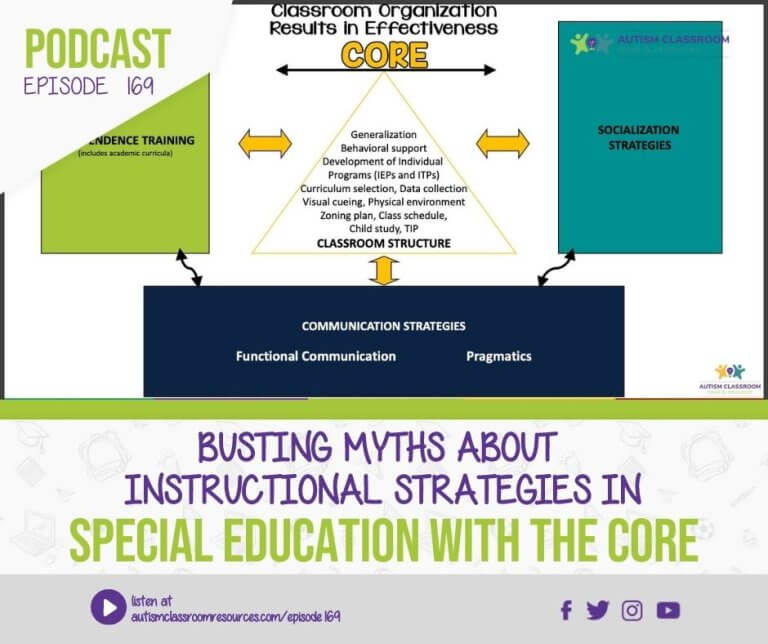

So let me bring this back to the CORE model for just a moment. What I want you to focus on in that model. And I’ll make sure there’s a picture of it on the website for this post, which you can find at autismclassroomresources.com/episode169. But you will see all of the interventions, all of the evidence based practices and interventions outside what I consider to be the triangle of the core. It’s a structured classroom.

You don’t see one kind of instruction. You see lots of different kinds of instruction on that model. In independence, we have different kinds of instruction, Discrete trials, pivotal response training, incidental teaching, reading mastery curriculum for teaching, reading with direct instruction. There’s lots of things that go in there. And for those of you that aren’t as familiar with the core model, the academics are in the independence section.

There’s lots of different kinds of communication strategies. There’s lamp, there’s Core Words, there’s the picture exchange communication system. All of those are strategies, there’s different strategies in socialization. That’s a very large bag of tools. But we need that large bag to meet the needs of our students on the spectrum. And even for our students who are just who are special ed and maybe don’t have autism.

Students wouldn’t be in special education if they didn’t need specialized instruction, that is the definition of qualifying for special ed. So that means that as educators, we need a wide variety of tools in our tool bag. But we get those tools by collaborating with other people on the team and continuing to grow our knowledge base. And we do it by going outside our comfort zone, by going to, you know, the special educator, the teacher, is the most probably the most diverse position that I see in the collaboration of people in special ed.

And the reason for that is they have to coordinate all these people who all come from different backgrounds, and different scientific areas. Their job is to figure out what the world they talking about so I can figure out how to implement it in my classroom. So some of you are already feeling this. But I think it’s really important that we all make sure that we are collaborating in a way that everybody can understand us, because we all need those large bags of tools.

That might mean that you’re collaborating with a speech and language pathologist who maybe uses her own jargon, or his own jargon, to describe what they’re doing. And you may need to ask them to explain it. And that’s okay.

It may mean collaborating with a behavior analyst, who, again is probably more like than the speech pathologist is more likely to use their own jargon, behavior analysts, as one of them have a tendency to really want to use our own jargon for some reason. And you may have to ask them what they mean.

So for instance, they might tell you that child needs verbal behavior analysis, to which you might go, yeah, he needs to be verbal. And then that isn’t really what it means. It’s a specific branch of ABA that teaches verbal behavior, both with pictures, with signs, with gestures, as well as verbal behavior, or verbal skills, using Discrete trials, naturalistic instruction, and other kinds of things. Using those same loops.

Don’t let other people’s jargon get you down. Always ask what someone means if you don’t know what a word means. I’ve worked with a large number of all different types of professions. And I have learned so much from all of them. But we all have a tendency to fall back on the language and talk that we’re used to, especially in the busyness of everything we do every day.

It’s kind of like when you talk to your family who’s never had a kid and special ed. And you start throwing early alphabet of IEPs and BIPs and FBAs. And you know, whatever the evidence initials are for those things in your district. And as my mother used to say to my sister, the teacher, and I don’t like, I don’t like talking alphabet, talk in English. We all need to talk it whatever our native languages, whatever our language is where we work. So that’s a big piece of it. Don’t let that intimidate you is really my biggest message.

When people are talking to you using terms that you don’t understand, just ask them what they mean, make them explain it. They should be able to explain it if they really understand that. Don’t get intimidated and feel that you are not knowledgeable, you may be doing something that looks exactly like that, but not have heard it described that way.

You just want to make sure that you’ve got this characteristic instructional loops, and that you’re closing the loop. And we’re using the loop intensively enough for our students to make progress.

So whether you’re dealing with a situation in which you have people coming in and saying my child needs early intensive behavioral intervention using Discrete trials, and that’s the only kind of intervention that should be used in students with autism. That’s not true. We make our decisions based on the student’s performance.

Now, if they come to me with data that they’ve used it and they’ve seen the change, we’re going to do it. It may not be the only strategy that we used, though. Most behavior analysts wouldn’t use it only one strategy either.

It may be a myth that I hear a lot in preschool. I did most of my work in preschool over the years. I work with all different ages consulting, but I was always housed in places that have preschool. And I think that you know, one of the ones I hear a lot is that we have to do a play based instruction, because play based is developmentally appropriate.

To which I often will say that would be true with a lot of other students, a lot of other special needs students. But for a student who has autism, he probably needs us to change his environment from the typical to make things more, make that beginning of that loop more clear to him. And he needs to learn the skills of how to play before he can use play as a way to learn.

Roger Cox from Project Teach had a really good quote that said, for students with autism, play is work and work his play. And I see that a lot with our students. They love independent work because they know what’s expected of them. They struggle in play, because they don’t know, that’s a whole other podcast episode. We base our decision on the data and the needs of the individual student and whether we had the hallmarks of good instruction.

So if that was too long, and you didn’t listen to it all, or couldn’t quite get the main points, as I meander through my stories, I will summarize. Different students need different instructional strategies. Some do better and naturalistic strategies, some do better was structured and structure with fewer distractions. Maybe like Discrete trials.

The common elements of good instruction are instructional loops. But make sure that you’re using all the parts of the loop. Make sure you are not forgetting to close the loop based on the student’s response. And that’s probably the biggest error that I see. And I think it’s also really important to make sure that you’re getting enough loops and enough practice for the student to learn the skill. Because one or two trials, or one or two loops isn’t going to do it.

Those instructional loops, transverse disciplines. Collaborate with other professionals. And don’t be intimidated by the jargon. We all have a tendency to fall back into it because many of us learn when we were sleep deprived, and it was drilled into our heads. So when we’re tired, we go back to what we had to memorize in grad school. So sometimes it’s easier for us to talk in jargon than to explain things. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s helpful or too useful.

Never be afraid to ask another professional what they mean by a term or a word. And they should never make you feel bad for not knowing. That’s your instructional loop. That’s how you learn and build your skills.

Ultimately, what we do know to be true is that there is no one size fits all special education or autism instructional strategy. We need to be making decisions based on the student’s performance and data. And while we need to use interventions that have a research base and an evidence base, we have no research that demonstrates which evidence based practice is better for which specific students. Our science isn’t there yet.

I hope that gives you some things to think about during your summer. If you’re listening when I’m recording it, it’s June. It’s a little heavy, but I thought it might work better in the summer when your brain is a little bit free of the day to day kinds of things.

I would love to hear your thoughts. So hop over to the free Facebook group and share your thoughts in the discussion there. And if you’re not a member already and you’re an educator, paraprofessional speech pathologist, you can join us there at specialeducatorsconnection.com.

I’ll be back next week with some exciting news and ideas for the special educator Academy. If you haven’t tried us out, come join us when we will be starting doing Setting Up Classrooms Bootcamp in July. Talk to you later.

Thanks so much for listening to today’s episode of the Autism Classroom Resources podcast. For even more support, you can access free materials, webinars and Video Tips inside my free resource library. Sign up at autismclassroomresources.com/free. That’s F-R-E-E or click the link in the show notes to join the free library today. I’ll catch you again next week.