Once we have the learner’s attention, our next step is to give the instruction. Let me preface this by saying I know that one of the biggest stumbling blocks for ABA is that we use our own language. I’m going to simplify the language as I talk about the parts of discrete trials, but I’m going to try to talk as well about what the language is and why we use it. I find I meet a number of teachers who want to know WHY we call things what we do (as well as many people who misunderstand why). So, I’m going to talk a little about what the instruction is and how it is conceptualized behaviorally. You can skip that part by skimming past a short paragraph or two to the part of the post where I’ll talk about what to do.

In discrete trials this is typically referred to as the discriminative stimulus, or the SD. (I can’t believe I just figured out how to make that d in html!) Some days, I think that we use these terms to confuse people and sometimes to make ourselves sound smart. But on other days, usually when I’m teaching my grad students, I remember there are some reasons that we use our behavioral jargon. So, here’s the reason we use SD. An SD is the presence of a cue and/or material in the presence of which a response is reinforced. If the SD is absent, that same response is not reinforced (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). It’s teaching the student to discriminate regarding when the response will be reinforced.

Let’s try an example. I’m teaching a student to follow one-step directions and one direction is “clap hands” (see my discussion below about choosing SDs). In the course of teaching, I was the student to learn that clapping hands when I say “clap hands” gets reinforced. Clapping hands just to be clapping hands and without the direction, or when I say “stand up,” does not get reinforced. It is teaching the student to listen to the direction and engage in a specific behavior (that in the past has been reinforced only in the presence of that direction). Discrete trials are essentially a situation in which some specific response is reinforced in the presence of specific directions / materials while another response is not.

OK, enough scientific mumbo jumbo. Let’s get down to what we need to know about the SD.

It’s important to know that the SD is not just an instruction. It is made up of the verbal instruction the teacher gives, any gestures used with the instruction (e.g., pointing), and the materials that are presented. Today I want to talk about what to aim for overall and the qualities of a good SD. Then I’m going to talk about instructions and materials separately in later posts.

1. Short and Clear

Your instructions in DTT should be short and clear. One of the challenges of DTT is that you are limiting the amount of information you are giving the learner. Give too much information and you are going to confuse them. Most students with autism have difficulty knowing what the relevant information is they need to focus on. For instance, if I say “OK, it’s time for you to sit down in this chair,” the learner with autism (and other disabilities) is likely to hear “chair” and only sit down when you use the word “chair.” So when you tell him “Go get me that chair” his will likely sit in the chair, because that’s the behavior that got reinforced when he heard “chair” before. It’s much clearer to just say, “Sit down” or even “Sit.” We don’t do this because we want to give commands, we do it to keep the distracting stimuli to a minimum. As the student begins to learn the association between the behavior and the words, we’ll start mixing it up (e.g., have a seat, go sit over there) so that he can respond to different instructions. We’ll talk more about it when we talk about the need to teach generalization.

2. Contain Only Relevant Information

This is similar to #1, but I’m going to take a bit farther. Grow and Leblanc (2013) suggest that when teaching vocabulary, you want to keep your words to just those that are relevant to the task. So, if the focus is on teaching the student to identify the color red, you would just say, “Red” and he would engage in some behavior like giving you the red card or pointing to red. Their point is that “Point to” is a different response and confusing when the focus is red.

Similarly we all may have met (especially the SLPs among you) that child whose parent tells us when we are testing a student that we are “asking it wrong.” This is because the child was taught with only the whole direction (e.g., “Give me red”) and you asked him to “Point to red” which to him is a completely different skill. Grow and Leblanc make the point that if you just teach “red” and you have already taught the student how to give or point to, “red” will be enough to generate the response you want and prevent the student from associating the carrier phrase (e.g., point to) with the correct response (e.g., point to always means give the red one). It’s a good and important point for many of our learners.

3. Make Sure Your Direction Matches the Skill

This is one that I see as an error frequently and it’s easy to get confused. When we are teaching learning readiness skills, we often teach imitation (doing what I do) and following one-step directions (doing what I say). When we are teaching imitation we say, “Do this” and we demonstrate (e.g., we clap our hands). When we are teaching one-step directions, we say “Clap hands” or “Clap your hands” and our hands are quiet (if they are not it’s a prompt, not part of the direction). It’s really easy to get confused (I’ve done it) and either give the model when you are giving a direction or give a direction when you should be giving a model. Make sure you are giving the right SD for what you are trying to teach.

Similarly, be careful not to say “Match horse” when you are handing him a horse card and the direction is to “match.” It’s adding information that isn’t part of the skill. The same can be said for materials. Make sure the student is reading you numbers in order rather than counting on his own. If you give him a file folder or number line, some students may just read the numbers and they are in order on the materials. That’s not the same as rote counting.

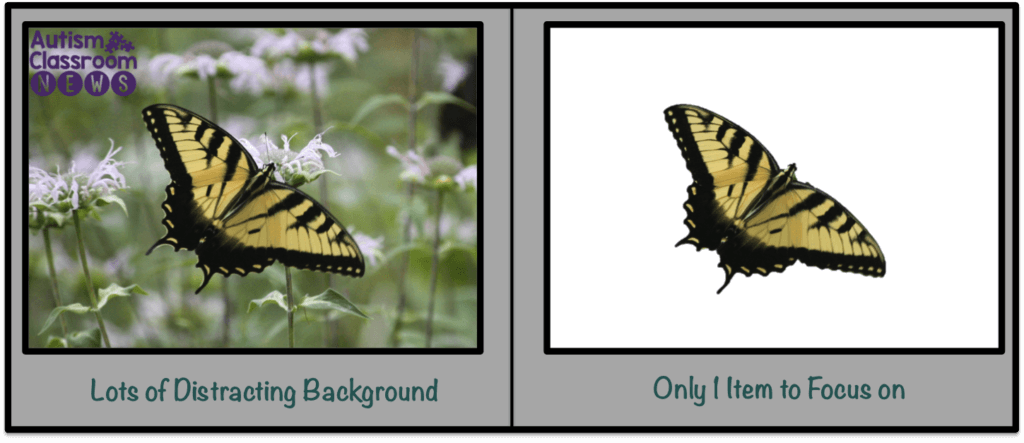

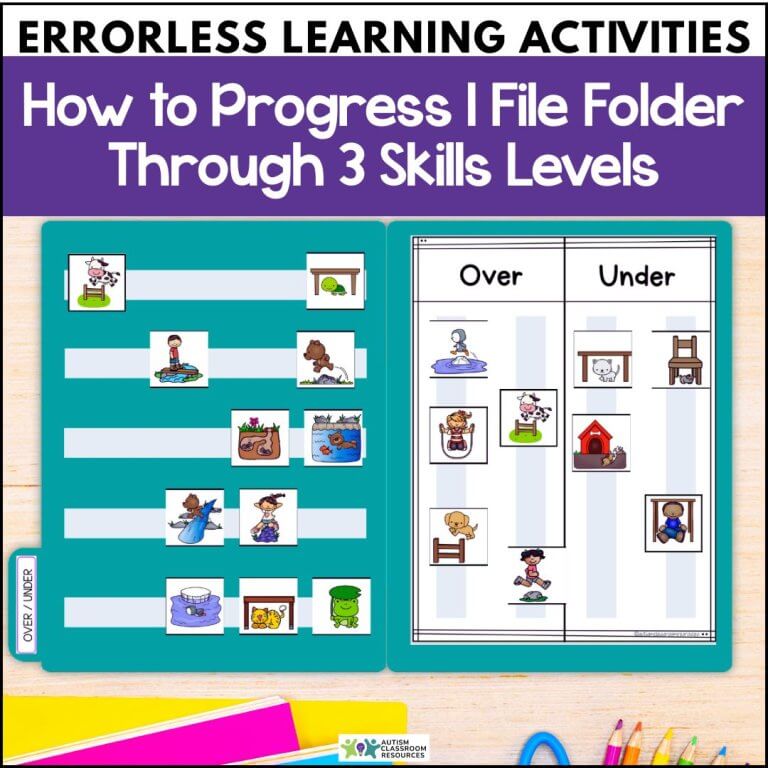

4. Make Sure Your Materials are Clear

You need to make sure the materials you use are only showing the thing you want them to identify. For instance, showing them a picture of a bunch of farm animals and trying to use it to teach them to identify a cow is likely to end up with the learner identifying any of those animals in the picture as a cow. Oops. Similarly, when we first start introducing materials, we want to make sure that the background information doesn’t distract from what the learner needs to attend to.

5. Make Sure the Materials are Age-Appropriate

I will talk more about this when I talk about choosing what to teach, but regardless of what you are teaching, it’s important to make sure that your materials are age-appropriate. Let’s take counting as an example. Younger students count colored bears or toys. If you work with older students, what could they count. How about coins, socks, or silverware? To get the most generalization of the skill to real world, use real things that the person sees in their environment. It will prevent you from having to reteach with new materials.

So, that is our start in discussing presenting instruction to the student. My next few posts will be focusing on this because we can really sabotage ourselves with this element.