To see the other posts in this series click HERE.

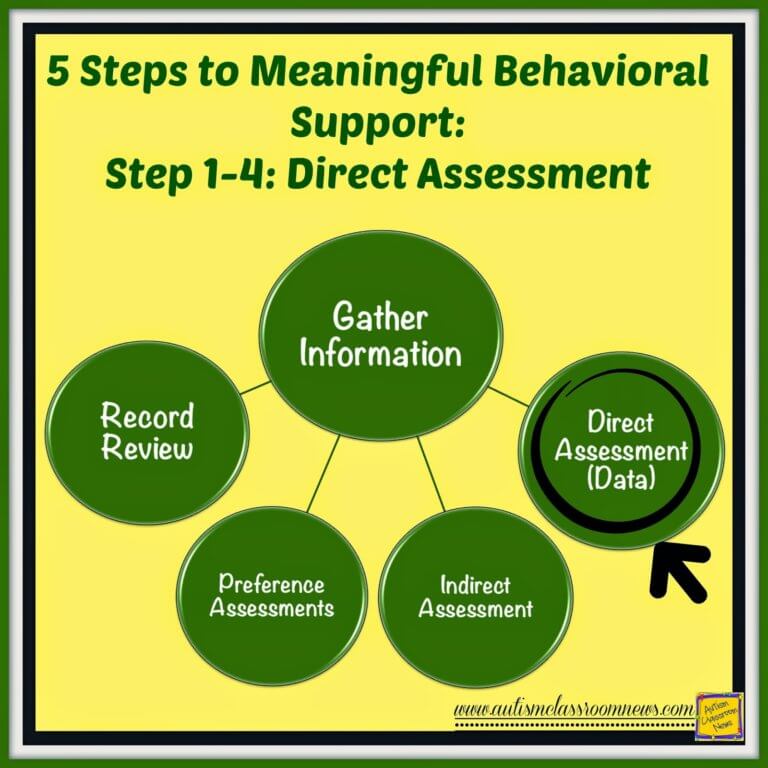

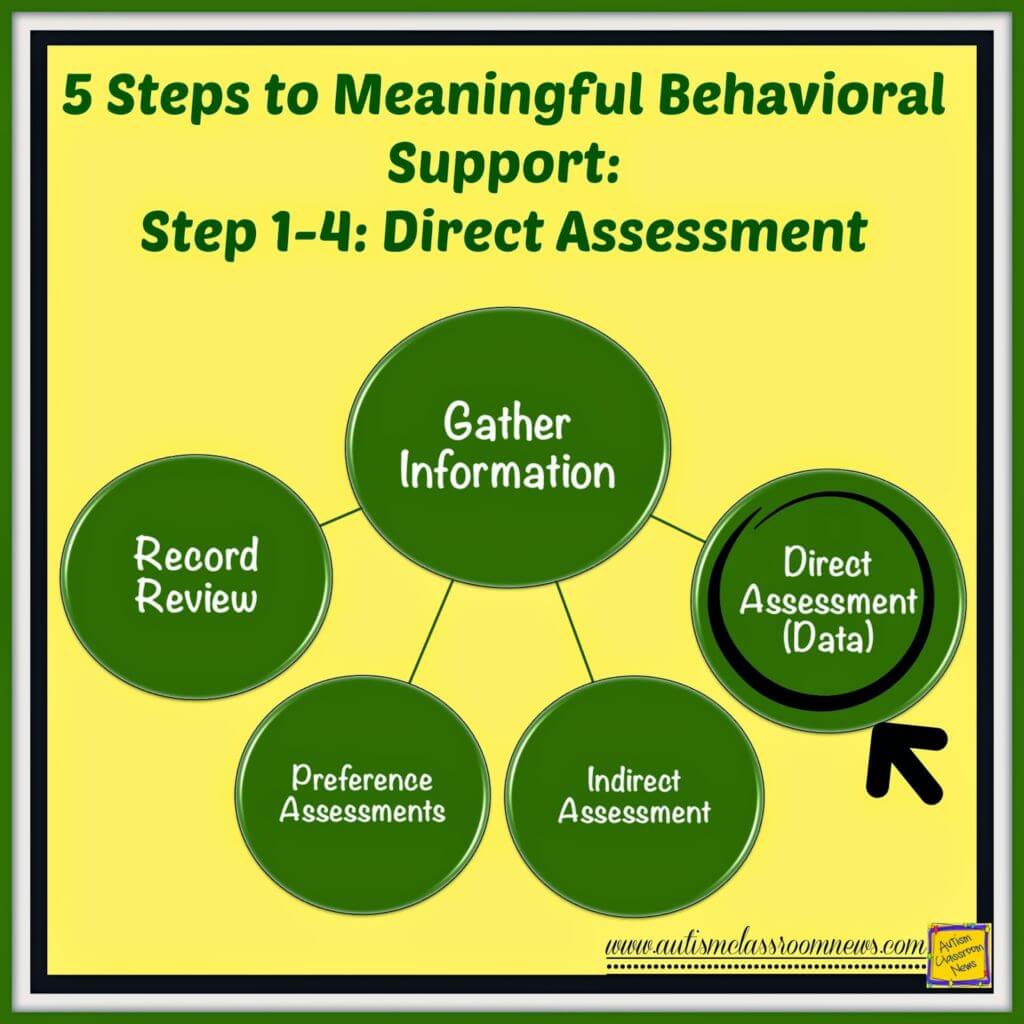

And this brings us to direct assessment of the behavior. Typically this involves taking data while observing the student in the natural environment or in an environment in which we may be manipulating some variables to see if the behavior occurs and/or increases. This is the true crux of most FBAs because data needs to be objective, clear and useful but also not take up so much time that it interferes with keeping students engaged in learning. But hey, that’s the easy part, right?

What? You say that’s not so easy? No, you are right, it’s not. To make the most of our time we want to make sure that the data that is being collected is the data that we actually need to use and that will help us figure out what to do. Taking data to have data is not what we are after–it has to help us figure out the function. If it doesn’t, ain’t nobody got time for that!

There are lots of types of data that we can take about behavior. We can take frequency counts where we count each time the behavior occurs. We can take that same frequency data and divide it by how long we observed and collected the data to get a rate data that we can compare across time periods. We can take scatterplot data where we record if the challenging behavior occurred in a specific time period of the day. We can take data where we record how long a behavior lasts (duration). I’m a data geek, so basically I could go on and on. However, the real crux of using data for decision making in this situation is that these types of data focus on the form, but they don’t tell us about the function of the behavior. And we know that FBAs are all about function rather than form. Those types of data will give us some baseline data (which I’ll talk about later) but they really don’t inform the FBA in terms of developing hypotheses about the functions.

Typically to trying to figure out the function, we need information about the context of the behavior–where / when does it occur, what was going on before it occurred and what happened in the environment after it occurred. This usually takes the form of Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence data or ABC data. However, like any kind of data, ABC data is only as good as what is recorded. Here are some thoughts about what you record when taking data for challenging behavior and describing events around it.

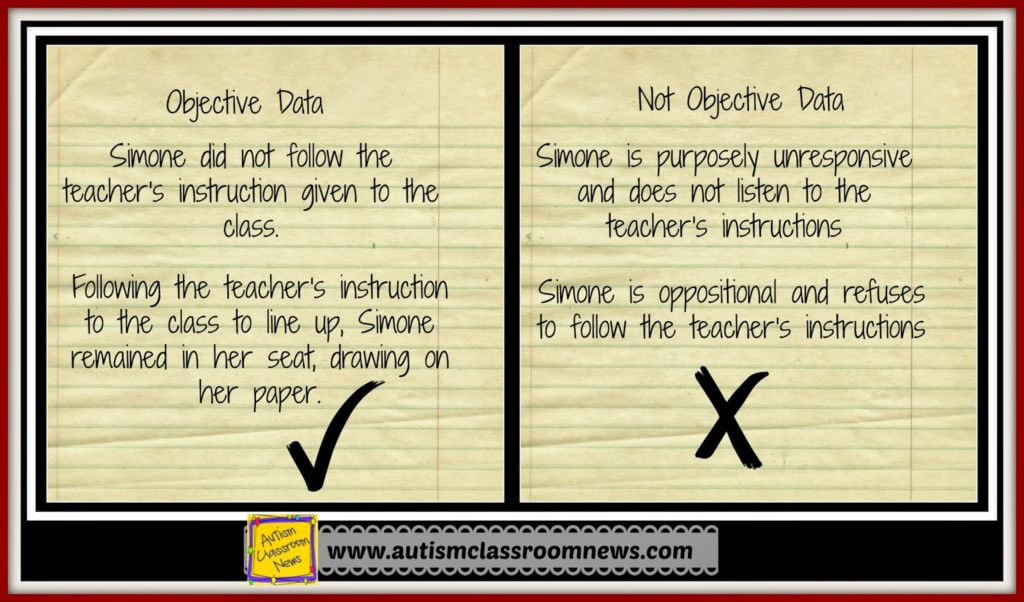

1. Record Objective Information

Taking data on challenging behavior probably one of the most difficult times to be objective. Challenging behavior makes the best of us emotional at times because we are frustrated, upset or just because we are having trouble figuring it out. It’s important to try to avoid having this come out in your collection of data. The language we use in writing about the behavior is as important as the information that we need to record. There is a big difference to someone reviewing the data to read the examples on the left vs. the examples on the right. The right two reveal a negative interpretation of the behavior that may or may not be valid. The left two simply describe what was observed. Remember that when taking data, “just the facts, ma’am” is the best way to go.

Similarly avoid making judgements statements about the staff, as well as the student. Remember that you will probably not be the only person to read the data. Imagine a parent reviewing the data, or worse a hearing officer in a due process. Everything you record on the data sheet becomes part of the child’s educational record, so always write with the idea that someone else is going to read it. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t record what you see a teacher do, in any way. However, don’t read into the behavior what may or may not be true. For instance, saying that the student raised his hand to answer 3 questions and the teacher did not call on him is much different than saying the teacher ignored him and never called on him. The first is objective and measurable. The second is a generalization and not objective because it puts your interpretation of the situation into what actually happened. Similarly the teacher asked him a question that she knew he couldn’t answer is different than the teacher asked him who the third president of the United States was and he did not know the answer. Certainly a pattern of questions he stated he did not know might indicate that the teacher is not asking questions at his level and might be deliberately setting him up for failure, but you certainly don’t know that because he was unable to answer one question.

TAKE AWAY: Keep Your Emotions Out of It.

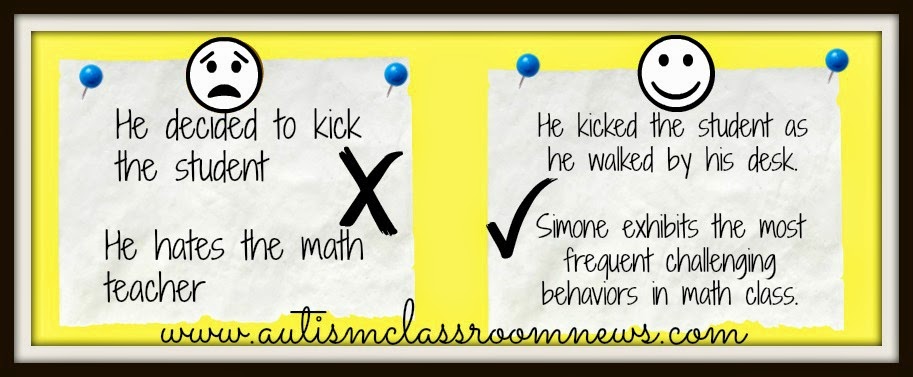

2. Write Only What You Can Observe

We all have feelings and emotions and I’m not debating that. However, we don’t know what someone else’s emotions are from watching them. Most people know someone who gets really quiet when angry and most of us know someone who throws things and screams. Same emotion-different behavior. Similarly we all think, but we cannot determine what someone else is thinking unless they tell us. Think about the difference between the two statements below.

He decided to kick the student supposes intent and a conscious decision on the part of the student that may or may not be there. Better to describe just what was observed–that he kicked the student. Similarly, he hates the math teacher is something you can only know if he actually tells you he hates her (and even then sometimes we all say things that we don’t mean or aren’t really able to express how we feel). However, we can know whether or not challenging behaviors are more likely to occur in the math class than in other areas. This might or might not have anything to do with his feelings about the teacher–it might be because math is his hardest class and he may love the teacher.

TAKE AWAY: If you can’t see it, you can’t know if it’s true

3. Don’t Replace Your Observations With Your Interpretation of the Function

For those of us who get that there is a purpose for challenging behaviors and they serve a function, it’s hard for us to remember that when taking data we need to just record what happened and not try to figure out why. When we say, “he kicked her because he wanted her attention,” we may or may not be right. It’s more precise to say, “he kicked her and then made eye contact with her and laughed” (which might indicate he was looking for a reaction). Essentially just remember that if we knew the function of the behavior, we wouldn’t need to take the data. Presuming the function when describing the behavior gets in the way of interpreting it differently which might lead to better results. Similarly don’t describe the function IN PLACE OF describing the behavior. For instance, don’t say, “he tried to get her attention” when what you saw was that “he kicked the teacher when she was talking to another student.” It’s OK to write what a possible function might be when recording the data but don’t use it in place of an objective description of what was seen happening in the environment.

TAKE AWAY: If we knew the function, we wouldn’t need to take the data.

This is an issue that will come up more, I’m sure, in future posts in the series. It’s important to remember that all of these factors should apply to describing the behavior as well as describing the environment and what happened before and after the behavior. I’ll talk more about that as we go through the elements that go into naturalistic data collection as well as provide some freebie data sheets that you can use to take ABC data in different ways.

Until next time,