In my last post I talked about some of the myths and truths about applied behavior analysis (ABA). One of the primary instructional strategies within ABA is discrete trials (sometimes called discrete trial training -DTT and discrete trial instruction – DTI). DTT is such a frequently used strategies for individuals on the spectrum that for some it has become synonymous with ABA (see myths in the previous post). The reason why DTT is frequently used dates back to Ivar Lovaas’ 1987 study that demonstrated for the first time that young children with ASD could make significant gains in IQ, adaptive behavior and overall skills through the use of intensive instruction using discrete trial instruction. For those of you who aren’t familiar with 1987 (i.e., might not have been born then), don’t tell me about it, it’s important to understand that educating students with ASD was MUCH different then than it is now. We didn’t know how to teach systematically in a way that could help them to learn to learn. That research and the big push of research that it brought about in the last 30-some years is in part why we are here. Since then our knowledge about how to provide instruction, what to teach, how to put it all together and more has greatly evolved to include a number of approaches and to combine with the knowledge and understanding of other fields like SLPs. I will talk more about the different approaches and curricula in the future. To see how much DTT has changed in this time period, check out the videos of DTT then and DTT now at the bottom of the post.

So enough reminiscing, let’s get to the point.

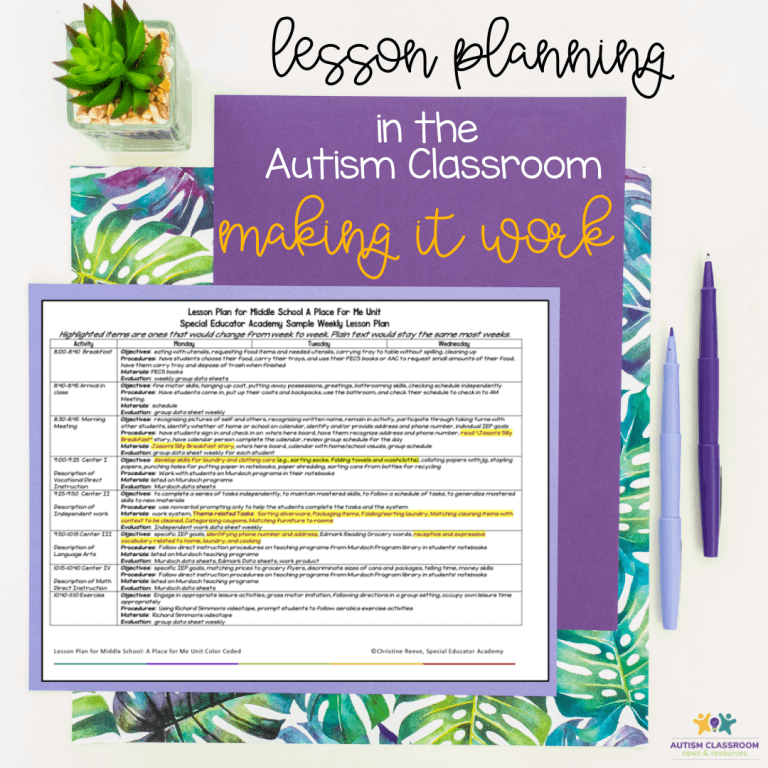

After all that, what is DTT? It is a very systematic instructional strategy. The first step is creating / using a teaching program that breaks skills you want to teach into small components to teach in sequential order. The trials are then used to teach the steps of the program.

A trial is made up of 6 primary components. 1. Gaining the student’s attention. 2. The instruction or discriminative stimulus. 3. Presenting the materials. 4. Prompting if needed for a response. 5. The student’s response. 6. And the consequence for the response (e.g., reinforcing the correct response, error correction). Then we repeat the process with another skill or the same skill depending on what you are teaching.

Essentially these elements are really what make up all good instruction. Good instruction involves breaking skills down into component parts, presenting directions and material clearly, using systematic prompts and prompt fading strategies, and effective reinforcement procedures for correct responses. Regardless of what and how we are teaching, instruction should be fun and engaging, and the student’s engagement (and performance) should drive our instructional decisions. Over what will probably be a long series of posts, I will break down the components of instruction and review some of the research about best practice from how we present instruction and how we develop it. Next up, what we have learned about getting the student’s attention.

Until then, check out the videos below. This one shows how DTT looked in the 1980s.And this one shows more contemporary DTT. Same systematic instruction, very different in implementation.

![Summer resources to help survive the end of the year in special education [picture-interactive books with summer themes]](https://autismclassroomresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SUMMER-RESOURCES-ROUNDUP-FEATURE-8528-768x768.jpg)