Welcome to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast, the podcast for special educators who are looking for personal and professional development.

Christine Reeve: I’m your host, Dr. Christine Reeve. For more than 20 years, I’ve worn lots of hats in special education but my real love is helping special educators like you. This podcast will give you tips and ways to implement research based practices in a practical way in your classroom, to make your job easier and more effective.

Welcome back to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast. I’m Chris Reeve, I’m your host. And we are all about how to help our students with autism and special education needs thrive as much as possible in the classroom.

And as we are deep into the holidays when I am recording this, many of you are probably struggling with some difficult behaviors from all the changes that happen in schools during the holidays, like holiday programs and fast schedule changes you weren’t expecting that all can really wreak havoc on our routine that we probably just really got started before, you know, November.

But good news, I’ve got a free resource that can help you with having your students ready for winter break and returning to school that I’ll share with you at the end of the episode. And some of what we’re going to talk about today I think could be helpful as well.

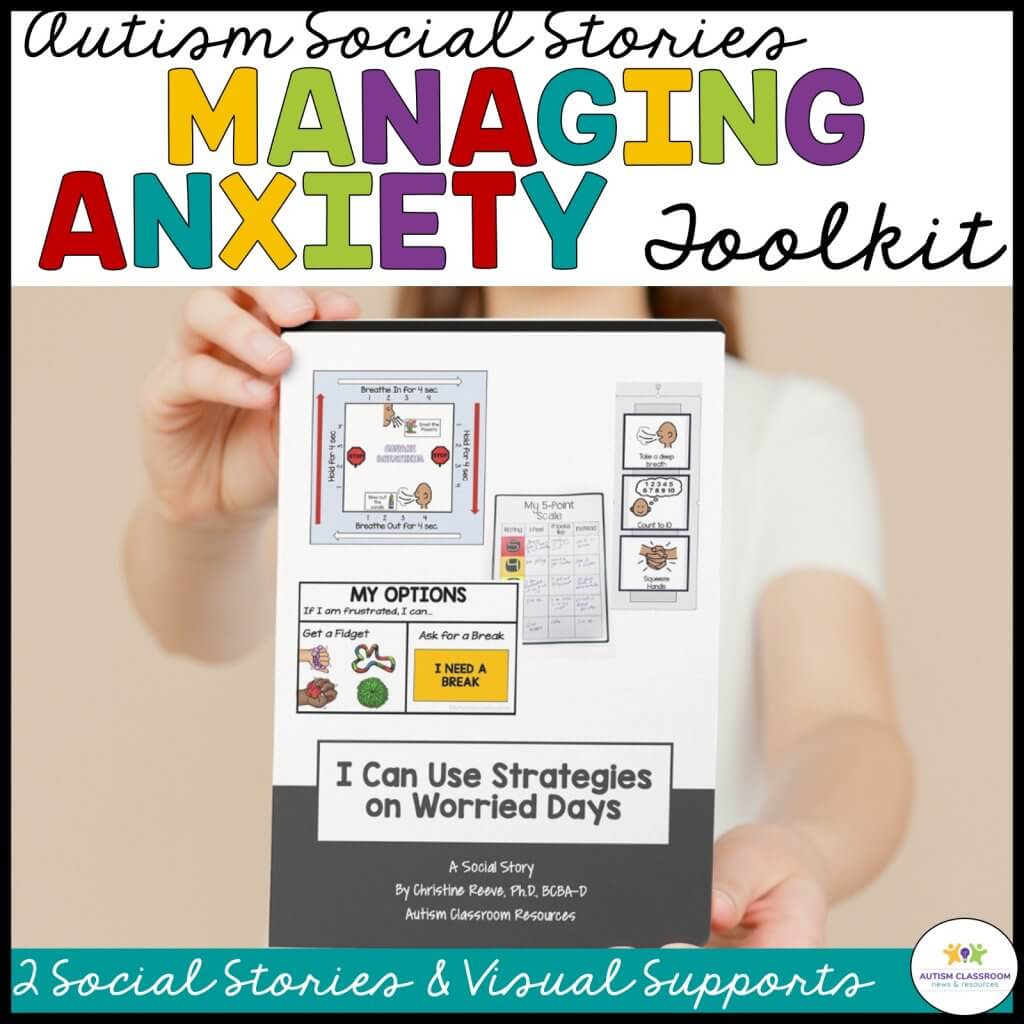

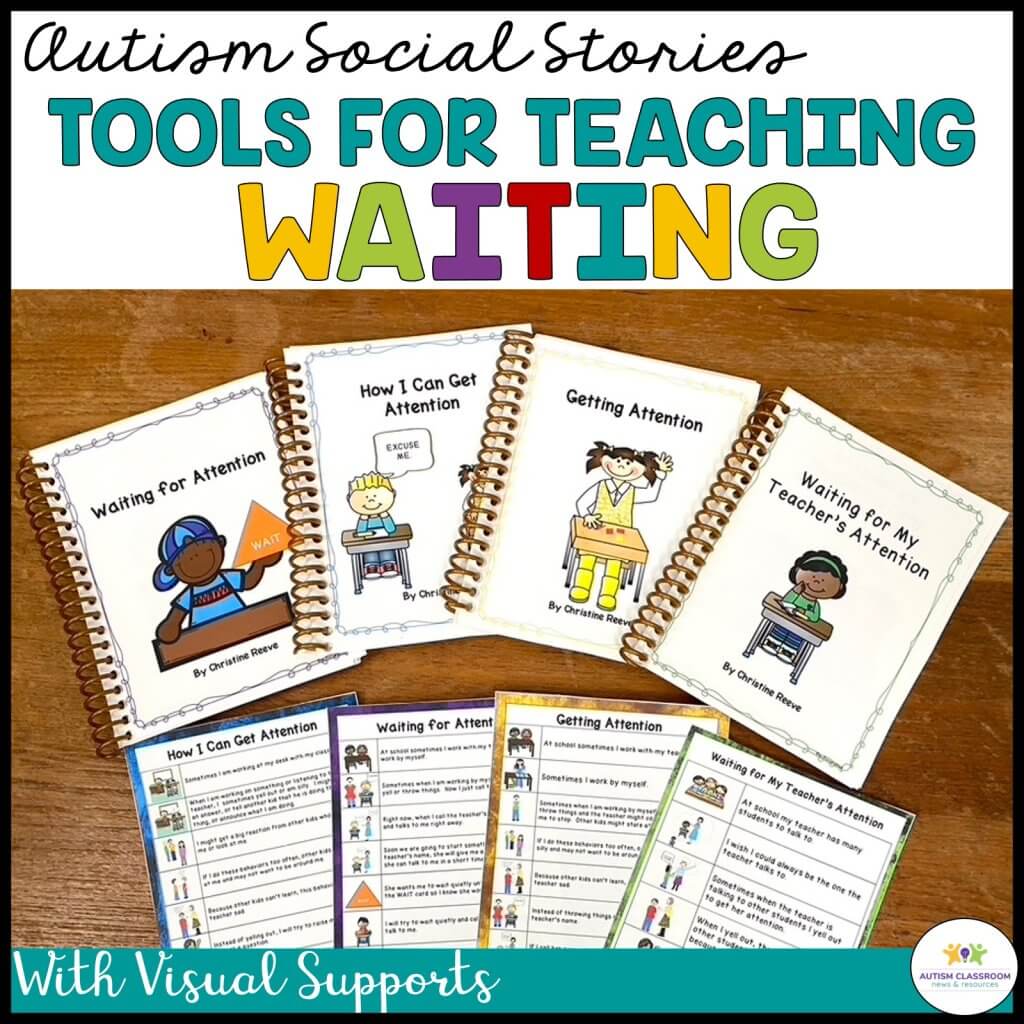

And if you’ve worked in the field of autism, or even more generally, in special education, you probably have heard of and used social stories. Sometimes we call them social narratives, sometimes we call them social stories. They originated as social stories. I love social stories, I use them all the time, I have a number of social stories in my store that I’ll refer to you at the end that I use as part of behavioral toolkits.

But I found over the years that they aren’t always used in the most effective manner by everybody. People are told to use social stories, but they aren’t always given a lot of information about how to craft a good social story, how to use it most effectively, and how and when it might be your intervention of choice. Partly because many people feel that, hear about them and they think that they’re kind of a magic cure.

Spoiler alert, they are not a magic cure. And some of them just think that it’s a story to tell students what to do. Like if we put it in the story and tell them that this is okay and they like it, that they’ll stop having behavior problems about something they don’t really like and, no, that is not what it is. And I’ll explain some of the elements that go into it as we go along.

So I thought it would be really good to have a couple of episodes focusing on the research of social skills, what they are, what they aren’t, what we know about how they work, because our research is really just kind of recent about them. They’ve been a part of what we’ve done since the 1990s. But the research is actually much more recent than that. So that’s this week. And next week, I’ll be back to talk about how we can use them most effectively, based on that research in a classroom context so they help us the most. So let’s get started.

Now social stories originated with Carol Gray in the 90s. And they were designed to be an individualized text or story that describes a specific situation from the students perspective. They weren’t necessarily specifically developed to address challenging behavior, although because of the difficulty that students with autism have with understanding others’ perspectives, that is sometimes the outcome that we are addressing.

So the social story gives information about where and why the situation occurs, how other people feel or react, and what their feelings and reactions may be prompted by so how are they viewing the behavior? What is their perspective, and it should give the student one or more options for what they could do in that particular situation to help cope with it. And by doing that is based on the information about the theory of mind and some of the difficulties that individuals on the spectrum have understanding other people’s perspectives and reading social cues.

So essentially, what is a social story? It is a story that is told in the first person. So I do this, I do that. It is designed to be supportive, instructional, and it is designed to be positive. So a social story should never be about why this behavior is bad, or why they shouldn’t do this, other than to give other people’s perspectives.

They guide the students through information about specific situations. Situations in which you think the student might have difficulty, new situations that they have never been in before, as well as sometimes problematic situations. And it’s designed to help the students to navigate the social situation that’s involved.

Now, Carol Gray, differentiate social stories from things like social scripts that helps a student what to say, or skill checklists. And I would definitely say that they are different. But the research literature isn’t always as clear about this.

Carol Gray has a specific structure that she uses. And I really think it’s worthwhile to talk about some of those different kinds of sentences.

Descriptive sentences are a large part of a social story. And they’re things that describe where situation occurs, who’s involved, what are they doing, why are they doing it. There’s also perspective sentences that describe how other people react or feel in a given situation. So what are other people’s perspectives.

And affirmative sentences that give insight about why this is an important social skill, or why society interpreted this way or things like that. So something that gives that kind of affirmation. They’re directive sentences, and they’re used very sparingly, because directive sentences are the ones that tell the student what they should do. I can, I will, I often use I will try. And I’ll talk about that in a few moments. But there’s a desired appropriate response. You don’t want that to be the majority of your story, because otherwise, it just becomes a direction sheet, not a story.

There are control sentences, which are strategies for recalling the information from the story. And they can be written by the student. She also talks about cooperative sentences where they provide information about how they can get assistance from others.

Now Carol Gray recommended in her book, that there are two to five descriptive, prospective, and or affirmative sentences for every directive sentence included. So that means that if I have one direction in the story, I need to have two to five of the other types of sentences. And I think that there is some value to this, although we have very little research on this specific composition, which I’ll talk about in just a minute.

There is some value to this, though, because it’s probably less overwhelming. When you have too many directive sentences, you end up with a story that just says you will do this, you will do that, you will do that. That’s a set of rules. That’s certainly not a story. And it’s certainly not something that is going to change someone’s behavior. If we could just tell them to do what they need to do, we probably don’t need a social story.

So let me give you some examples. This is a story about being quiet while waiting.

I go to kindergarten in Mrs. R’s classroom, that’s a descriptive sentence. Sometimes in school, I have to wait for the other children to finish their work before we do the next activity. Sometimes waiting for them is hard for me. So that’s a descriptive and a prospective sentence for the student’s perspective.

Sometimes when I’m waiting, I will talk to myself. That’s describing the behavior that we’re seeing. When I talk to myself, other kids can’t hear the teacher or do their work. That’s a prospective sentence about why this might be bothering other students. My teachers want me to be quiet while in waiting. When I feel like talking, I could ask Miss N to give me Koosh or toy to play with, or I could just talk to her. Those are coping statements. So those are strategy statements that the student can use in replacement of the challenging behavior.

If I’m quiet during waiting, then I earn a token. If I earn X tokens, I can pick a fun activity. So that’s kind of the outcome of choosing this replacement behavior. My teachers will be very proud of me if I can be quiet. So again, we’re back to a prospective sentence.

So, “When I feel like talking, I could ask,” that is our director statement. That is what we want him to do. So the rest of them are descriptive, prospective, other types of sentences.

So what does the research tell us? Well, areas that have been researched that social stories have addressed include increasing social skills, introducing new situations, reducing challenging behavior. There’s actually a couple of studies looking at that increasing appropriate behavior. There’s a study by Delona and Snell, and I have a list of all of the research resources as a swipe sheet that you can download in the show notes for this episode, teaching functional skills and choice making.

So they’re used for a lot of different kinds of things. They have been rated as an evidence based practices by the AFIRM modules and the group that does that evidence based practice, Look, they found that the majority of studies were conducted in a school setting, one was done in a home setting, but many of them were done to teach social skills, address behavior, and good communication. National Autism Center has also found them to be an evidence based practice as a story based intervention.

So none of this is specific, necessarily to Carol Gray’s methodology. In 2011, test et al. had six studies that found the social stories to be effective or very effective, 12 studies where the methodology showed that they were ineffective at making meaningful changes. And I’ll talk for a little bit when I get done talking about the research about some of the things that make interpreting this research sometimes difficult.

In 2018, Qi et al. did a meta analysis where they looked at lots of different studies that have been done on social storage. And they found that out of the 22 studies they looked at, seven of them had strong evidence of effectiveness, four of them followed along longer and found strong maintenance of the skills following the social story. So that was a really good finding. They found and concluded that social stories were effective for decreasing challenging behavior, but that they were less effective for increasing social communication and skills.

So they also noted that looking at the different participants across the studies, social stories may be more effective for some individuals than others. And I’ll share with you kind of my clinical viewpoint, when I finished talking about the research.

leaf et al. found three out of 41 single subject designs had convincing evidence that supported social stories, 17 Out of those 41 showed partial effectiveness, and 21 of them did not have convincing evidence of effectiveness.

Now, it’s important to recognize they were only looking at single subject designs, which I love, because I’m a behavior analyst. And we do a lot of single subject designs in our literature. I also love it because I know how incredibly different our students in special ed are. And I value that this works for some and not for others.

They used visual analysis to see if there were convincing evidence of this. And one of the things that they noted was that it’s very difficult to assess the effectiveness of social stories, because they are rarely used in isolation. We rarely use a social story by itself. We use it with visuals, we use it with a reinforcement system, just like the one I just read you that he earns tokens and earn something for following through on the expected behavior. But that makes it very difficult to tease out what impact the social story has on it.

So they also don’t always use the same type of social story. So some may use one that follows Carol Gray’s model, some may use a more directive model. There’s a wide variety of behaviors and skills that are targeted by them, too. So those are some of the things that make the research base in this area really difficult to use.

Now, I have used social stories with many more people who do not have autism. I do use a lot with my my students that I’ve worked with with autism, but I’ve used it a lot for other types of students. Students with emotional behavior, disabilities, students who have attention deficit skills, or who need some help with executive functioning. And I found that for some of the students that’s really effective. There’s no reason to assume that this is only an ASD kind of intervention. But there is less research on non ASD participants.

Benish and Bramlett found that it may have some effectiveness for decreasing aggressive behavior for young preschool students in Headstart. So those are typically be kids that didn’t have identified disabilities. We do have some research that is emerging on it being used.

Zimmerman and Ledford did a study there were they did a lit review. There were eight participants where no disability was identified, six that had comorbid hearing and language impairments, five participants had unspecified behavioral issues, two had language impairment, one was considered educable mentally handicapped, which was it’s an older 2017 study. One participant had hearing vision and speech impairment and one had multiple diagnoses including obsessive compulsive disorder, and ADHD.

All of these participants of these studies focused on using the social stories as an antecedent intervention for challenging behavior. And that’s really the category it fits in and how most people have classified it. They found that one study had high rigor and positive effects, three had moderate and positive effects, three, there wasn’t enough rigor in the study to really be included.

So we want to be careful when we’re using social stories with other populations that have limited research. But there are mixed results for those populations, there are mixed results for the ASD population as well. So it’s clear that there are some students that they work better than others.

And I will kind of leave the research with this story. I have used social stories for a long time, I have some students for whom they are extremely effective. And I have other students that it just didn’t work. I’ve had students that want to keep the social stories, so they can go back and read through them, and review them on their own. And that has been very reinforcing for them and helpful for their behavior.

I have had a student that I really felt like social stories were like magic, to the point where when we would find an issue for him, I would literally go and write a social story on the whiteboard just to get through that issue. And then he would, we put it on paper, and he could look at it later. And for him, it really helped him to understand what people were expecting of him, why they were expecting, and when we did that, it seemed to just click for him. And the behavior didn’t always go completely away but he began to understand and use some of the coping strategies a little bit more.

So again, I think there are students that are very effective with them, and there are others that you’re going to find they aren’t. Typically, because in a clinical setting, we’re not going to say, well, I’m going to do social stories only and see if they work. Typically, we want to address the whole of the behavior. social stories would be part of a set of antecedent strategies, strategies we put in place to prevent behaviors from happening. And if you go back to any of my episodes on behavior, I’ll try and put a link to one where I’ve talked about antecedent intervention specifically.

So as I mentioned, that’s kind of a quick and dirty summary of the research. And next week, I will be back and I will have specific suggestions for how we use them in the classroom, kind of what does research tell us in terms of how we can implement it, but I didn’t want this episode to go on any longer because it’s not a time of year where we have a lot of free time.

So you can find a number of social stories that are part of behavioral toolkits. Usually they have visuals and other supports with them in my store at autismclassroomresources.com/socialstories, all one word. And I also have a free social story on winter break. It has calendars in it that students can use to track when they’re going to get out of school, when they’re going to come back from school. And their black and white coloring books. So they’re really easy to send home is a PDF to the family to use for them to be able to know when they’re going to be coming back to school, and what’s going to happen in that time because their routine is changing. So you can grab that freebie also in my store at autismclassroomresources.com/winter-break.

And I’ll make sure those notes are in the show notes as well. I will be back next week with a new episode where we’ll talk about practical tips for using social stories. So I hope you’ll be back for that and I’ll talk to you soon.

Thanks so much for listening to today’s episode of the Autism Classroom Resources podcast. For even more support, you can access free materials, webinars and Video Tips inside my free resource library. Sign up at autismclassroomresources.com/free. That’s F-R-E-E or click the link in the show notes to join the free library today. I’ll catch you again next week.