Welcome to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast, the podcast for special educators who are looking for personal and professional development.

Christine Reeve: I’m your host, Dr. Christine Reeve. For more than 20 years, I’ve worn lots of hats in special education but my real love is helping special educators like you. This podcast will give you tips and ways to implement research-based practices in a practical way in your classroom to make your job easier and more effective.

Welcome back to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast. I’m Christine Reeve and I’m your host. As we are approaching February in what must seem like the longest year in the history of time, we are shifting our topic of morning meeting to talking about life skills classrooms. This won’t be a terribly abrupt shift since we shifted from talking about age respectful activities for older students last week in morning meeting to life skills classrooms this week. However, I have some myths that I really want to bust about life skills because it turns out that while we all might think we know what the term life skills means, it doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone. It doesn’t mean the same thing to every school system or to every parent. That’s where it sometimes gets us in trouble because when we all aren’t talking about the same thing, that’s when it all blows up.

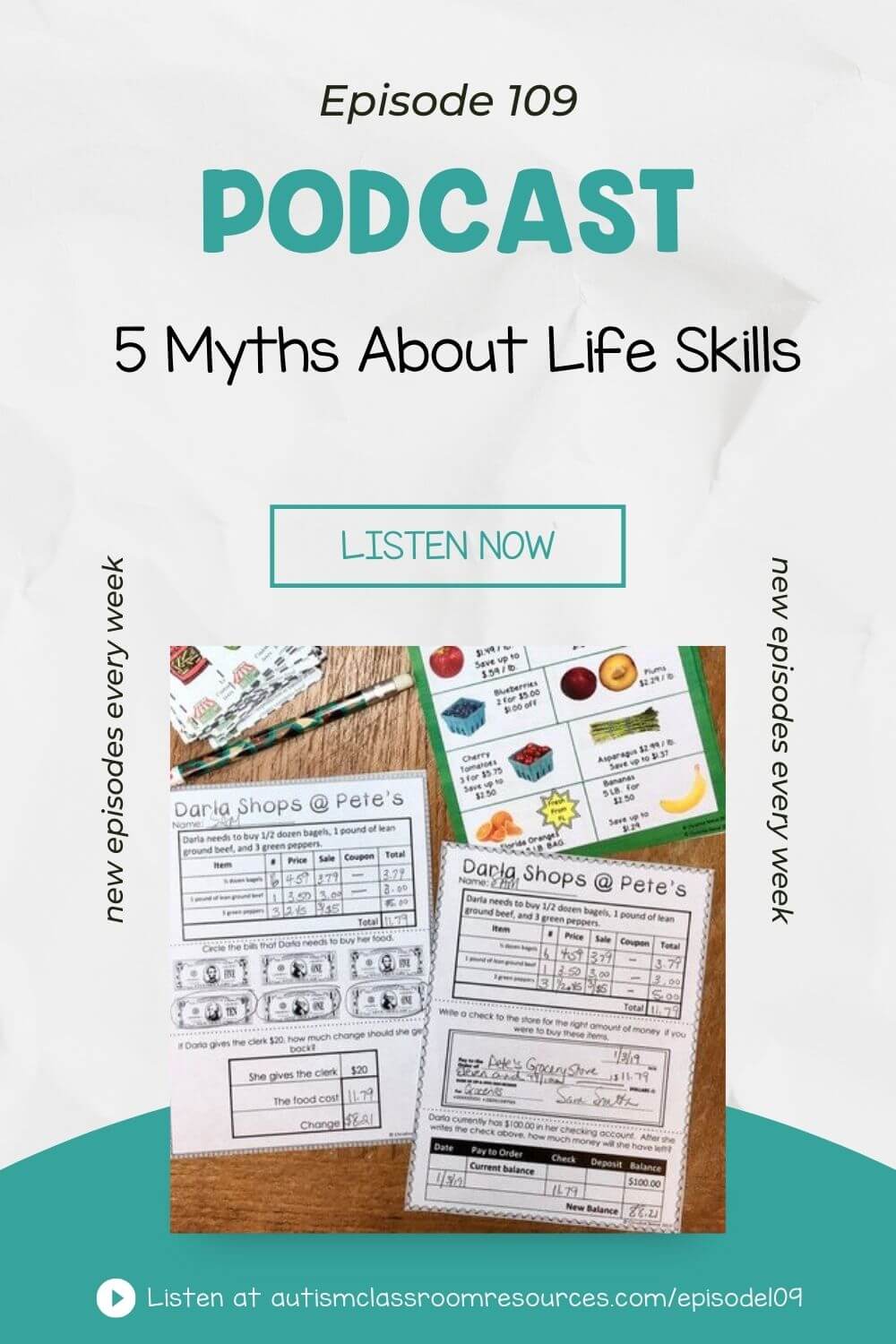

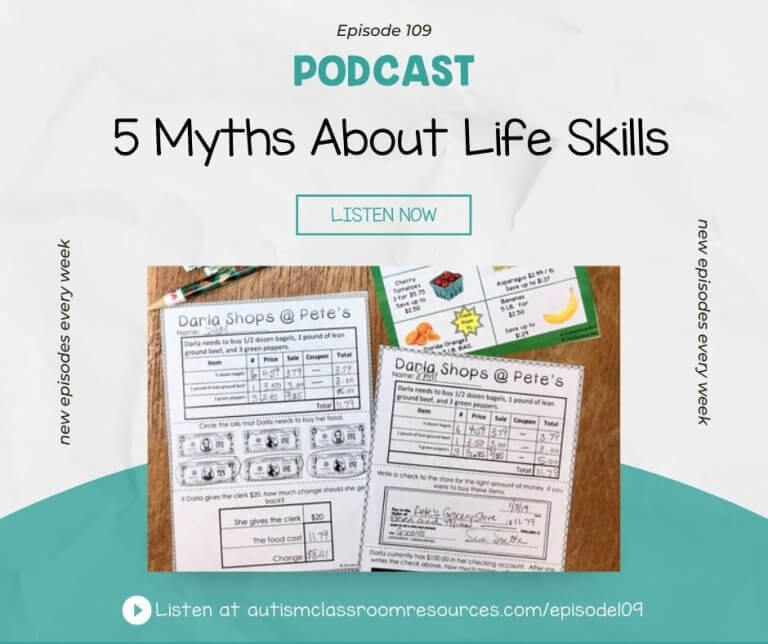

As we kick off this mini series in February about functional skills or life skills or functional life skills, I thought it would be really helpful to eliminate some of the myths that people think about life skills. “I’m looking at you. He’s too high functioning to need life skills,” and some of the misbeliefs, I’ll call them, that people have before I start talking about how we can make sure that our life skills programs for all of our students from preschool through adulthood—because yes, I said preschool—meet our students’ needs. Before I get started, just let me share. I’ll have some links to posts in the blog to help address some of the things that I’ll bring up. I’ve got some free activities in the Resource Library and my store, including some life skills, Valentine’s activities because some of the myths I’m going to talk about next week are that life skills activities do not need to be so grown up that they’re boring. Older students should get to have interesting materials too, but Valentine’s will be done by then, so grab them now at autismclassroomresources.com/episode109. Now, let’s get started.

I tend to use the word functional a lot when I talk about some of our classrooms. Functional to me means that the student can use the skill after it’s mastered and it improves their life. Essentially, it’s a skill that leads the student to more independence, leads them to the next academic setting to future learning or to an employment setting. Now, what are life skills? Interestingly, life skills can be used to refer to a functional curriculum that’s focused on employment, independent self-care or other transition skills. Sometimes, it describes a program of specific explicit instruction of daily living skills. Really, life skills can mean a whole lot of things. I had a college roommate who was brilliant but her mom came up to me on parents weekend and told me that she had brought her daughter laundry detergent, and showed her how to use the washing machine for the first time. I thought this was odd. I had done my family’s laundry when I was in high school. She had realized that her daughter hadn’t washed her clothes for a whole month because she didn’t know how to do that. That might have been a functional skill to learn before going out of state to school maybe, but life skills in no way should be limited to just daily living skills and self-care because frankly, those aren’t the only skills that I need in my life.

If I can feed myself and dress myself, yes, those are very important things to do. But if I can’t buy the food that I’m going to eat, I’m still going to be dependent on others to get that food to feed myself. I think I would still have some life skills that I would need to learn. There are, surprisingly to me, a lot of misunderstandings and myths that have developed over the years about these concepts. I want to tackle five of them today and set the record straight. First, “He’s too young to work on functional skills.” All students benefit from learning life skills in a functional way but not all students need explicit instruction to learn them. Typical students learn by imitating. One of the play skills that we see toddlers age three to five do is imitating the skills of their caregivers. They pretend to sweep and cook, and lots of other daily living skills. Many of our students with significant disabilities miss that phase. They don’t learn effectively by watching this, just a couple times. They need more explicit instruction.

It’s never too early to start teaching life skills in a functional way. It certainly doesn’t mean that it’s all that we teach. However, we can teach those skills explicitly alongside other academic skills that we’re teaching. In fact, I’ll talk about that in one of our episodes of how we combine academics and life skills. We could actually make some of our academic skill instruction more functional and meaningful by teaching and using the skills in a functional way. Because wouldn’t it have been nice if geometry had been taught with more real life examples and less X,Y? Wouldn’t it have been nice to figure out the area of the floor to know what size rug to buy instead of using X and Y for all of our examples?

Here’s another one of my favorites, “His time is better spent on academics, not functional skills.” That misconception stems from the idea that programs have to be all or none. They’re either academic or functional. That’s not the case. In fact, a strong instructional program focuses on both academics and the practical application of those academics. For some of our students, skills about how to dress themselves, care for themselves, manage themselves in the community are going to be just as important as reading and social studies. But since it’s not an either or proposition, we need to think about how to combine the two for students who need explicit instruction in both. We should always be asking, “How can I make this reading activity functional for the student?” That doesn’t mean we only teach him sight words or signs. Instead, it might mean thinking about all the different ways that he might use his reading in the environment.

For instance, students need to read the web to gather information. We all need to read recipes, the news and letters, or at least emails, that come with information in them. We also need to introduce students to reading for leisure, which is where fiction comes in. To gather information and understand all that they have read is going to be a crucial skill in all of that. Don’t limit yourself to a “life skills program” or an “academic program.” Be creative and combine the two to make it a functional application of the skills. As I said, I will talk more about that in an upcoming episode. I have a post that talks about the process of teaching content standards that might be helpful in jump starting this. I’ll make sure that that link is in this episode blog post as well, along with a free weather activity that’s designed to combine life skills, what clothes I should wear for the weather, with reading skills, looking it up on the web and using technology, and reading to find the answers.

Next up: He’s too “high functioning” to work on life skills. That might be the issue I hear most often and the issue that is most off target. I am putting high functioning in big air quotes there because I don’t really know what that means. People throw that term around and I found that everyone has a different definition. It’s really not a good way to describe people to begin with. However, I see this a lot in the autism community. If a student is in the general ed classroom, in general ed standards, we tend to forget that he might still need explicit instruction on daily living skills and daily life skills. These are often the biggest issues that face those students when they leave high school. We hear that all the time, “He can do the work but he can’t handle the environment. He can’t get himself here on time. He’s not dressed appropriately.” I have brilliant students that don’t know how to use a paperclip. No one taught them these things because they’re “too high functioning.” I was taught those things as a child, so I guess I wasn’t high functioning enough.

In addition, most of our students can do the work of the job and we can train them to do the job itself. It’s the soft skills, like social skills, independence, self-monitoring that are problematic for them. Life skills and functional skills are part of teaching a student to be independent, and that includes those things. SMART is not enough. Just having academic skills does not help your students be employed successfully or open community doors to them. I’ll get off that soapbox now and let you think about that.

Number four is when someone says, “I teach functional skills when I notice a problem.” That’s great but that means that we’re going to have a lot of problems that happen after you know that kid that just didn’t come up. We can’t wait for the problem to happen. We need to do it proactively. Waiting for the problem to happen meant that my high school roommate had dirty clothes for a month and she smelled. That’s not something you really want a college freshman to do. We don’t always know that. Many times, a school is the best equipped place to teach new skills for many of our students. I’m going to talk about this at number five, too. We can’t wait until we see a problem because we may not see it. It may happen at home. Instead, we want to have a programmatic curriculum that tells us what skills the student should have upon graduation to be successful. I have a post that reviews four such curricula. I’ll make sure that is in the blog post, along with the link to a life skills freebie for Valentine’s day. It’s in my store. You can find all that at autismclassroomresources.com episode/109.

Finally, number five. Let’s talk about the biggest myth I hear. I always save the best for last, don’t I? “Functional life skills are something the family should teach at home.” Now, this is one that I’m biased about and I’ll be upfront about it because I am the sibling of an individual with autism, and developmental disabilities. Given our age, most of her functional skills were definitely taught at home by my mother because she went through all general ed. Nobody knew she had a disability. Some of my earliest memories are of riding in the car with my mother in the evenings, following the city bus to make sure that she knew how to make a transfer without getting lost or panicking. That was our job. Now, my mother was trained to be a teacher. That’s what she did before she had kids of her own and I came from a family of teachers. But that is not the case for most of our students. There are a ton of issues with trying to teach new skills at home that probably warrant their own podcast all by themselves.

Home is not as structured, so it’s harder to set up. There are emotional overlays that make consistency in instruction really difficult. I say this as a family member. For instance, I will tell you that teaching life skills to my sister, my mother was always the teacher. Their relationship paid the price for it over time. There is such a difference between teaching as a family member and teaching as a teacher. I can’t even tell you I would be here for another hour at least. I’m not saying that some instruction in life skills shouldn’t and couldn’t be done at home. I certainly don’t mean to imply that the school has to be responsible for all of it because it shouldn’t, but we do need to partner with families to help them generalize skills that we might introduce in our classroom because if we think about it, we are the experts as the school in instruction. If we want to claim that mantle, we can’t then say, “Oh, but you have to teach this. You’re on your own.” If we want to take that mantle of being the experts, then we gotta take it. We can’t take it for some things and not for others. We can’t expect our students, who we, as trained professionals, sometimes struggle with, to teach new skills at times, to learn naturally from their parent’s instructions on all skills.

Sometimes, school is the best place to teach new skills because there is one thing that I can guarantee you. If you walk away with nothing from this podcast, I hope this is it. You have more than one student in your classroom who will perform skills for you that he will never do for his mother because I guarantee you, there are things that you will do for other people that you will never do for your mother. I will leave you with that thought. You can find links to all the things we talked about at autismclassroomresources.com/episode109. If you want more ideas, tools, and topics on life skills and ways to set up your classroom, definitely come check out the Special Educator Academy at specialeducatoracademy.com. I hope that you will come back next week when I will be telling one of my favorite stories about life skills classrooms and how they impacted the materials that I make in my store. I hope that you have an amazing functional week.