Sharing is caring!

In talking about replacement behaviors, probably one of the replacement strategies that most challenge teachers is how to replace behaviors that serve to escape from situations. It goes against our grain to teach a student to “get out of” the work we are trying to teach him. It goes against everything we are told by our supervisors and parents. I think this is becoming particularly true in our “high standards” age. I realize when I tell teachers that we should let a student “choose” not to complete something that this seems to be counter to her purpose in her job. I get it. I really do. I promise. And yet….

Yes, I ask them to do anyway. However, if you do it right, you can go from getting out of work to getting back to work pretty quickly. And there are some good reasons to do it. First, how much work are you getting done if the student tantrums through the whole work time or social time, or whatever time the challenging behaviors take place? Second, in the long run, you can get more work done when the behaviors have decreased and you have taught the student to do something before taking a break. Third, it’s a lifelong communication / regulation skill that you are teaching. Given that most of our students have difficulty maintaining a job because of their behavior, not because they aren’t capable of the job, teaching communication and self-regulation skills early on is critical for long-term success. So, put learning the communication skill into their IEP. It’s an enabling goal that will serve them well long-term.

OK, so now that we’ve taken care of that, let’s get down to the nuts and bolts of how to teach the student to ask for a break and then learn to work before he takes the break. This will get a little long, so if you want, you can go to the end of this where I have a protocol for teaching break requests you can download for free.

Choose Communication Form

This is going to be similar to how you choose one for gaining attention from this earlier post. Here are some things to consider:

- Choose a form of communication that is easy for the student to use. (Remember when I talked about efficiency being an important component of choosing replacement skills?) If a student isn’t using speech frequently or functionally, it’s probably not easy. You might want to use a speech-generating device for easy access or a picture exchange for portability. You will always pair it with speech, so most students, if speech works for them, will make this switch pretty quickly in the learning process.

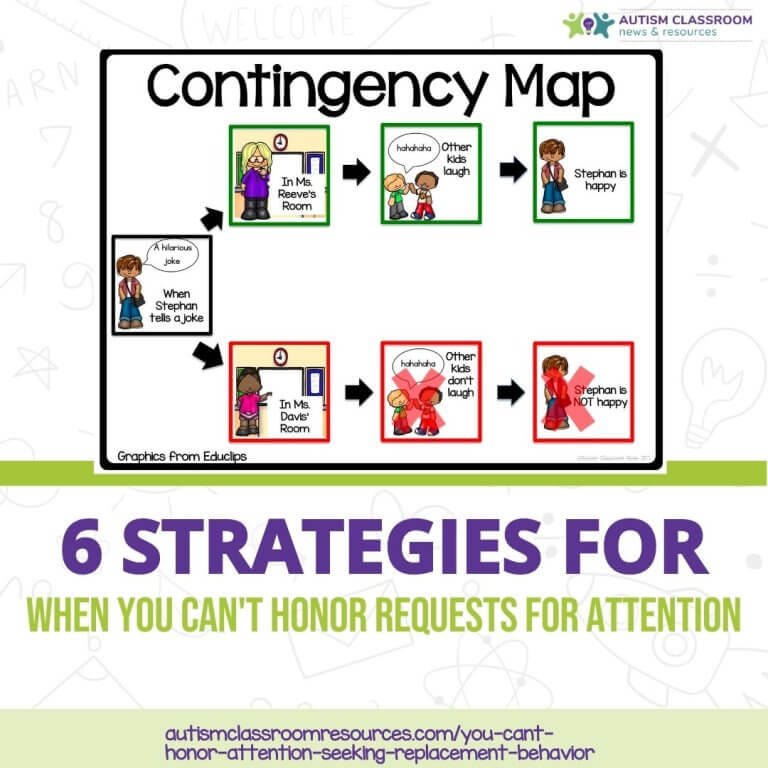

- Choose a phrase or script to be used as part of the communication that reflects what you want the listener to do. Most listeners when hearing a student say, “I don’t want to,” will reply, “You have to.” So while that accurately expresses the communication, it probably won’t work in as many settings. That’s why I like the term, “I need a break” as people are more likely to respond to that with an understanding that the student will come back to the task. However, I also really love SuperpowerSpeech’s Chillville. I have taught kids to say, “I need to chill.” And those I work with in the South have taught students to say, “No, thank you.”

- With that being said, when teaching, if the student adopts his/her own phrase, honor that as well. It doesn’t have to adhere to your script, particularly at the beginning. I have some kids who will say, “No math” or “No writing.” We honor that.

- Finally, choose a communication form that you can manually prompt. The prompting will be important so that the student begins to learn the relationship between asking for a break.

Define a Break

I think I will write my next post about this because it’s a question that really depends on the student and the situation. However, generally, you can choose to have the student leave the area (e.g., escape behavior was to escape the cafeteria) or just remove the task that is the common antecedent (e.g., math homework was the common antecedent). If you want the student to stay in the situation, just remove all the work materials so that the cues are clear about the expectations. Breaks can be short (e.g., 2 to 3 minutes) or you could have a student who needs longer to pull themselves together. Just make sure that the team is all clear on what a break will look like so that it’s consistent.

Teaching the Break Response

Just like with teaching an attention-seeking communication, you want to set up a time and place where you can focus your attention on the student with the common antecedent of the challenging behavior. For the purposes of example let’s say the common antecedent is writing (since so many of our kids struggle with it).

- Tell the student just before you present the writing assignment that he can ask to chill / for a break and he can [describe what the break looks like]. For a higher functioning student you could use a social story for this. You can find a social story in my I Can Stay Calm set of social stories and supports on TPT (as well as break cards you can use).

- Present a writing assignment and immediately prompt the student to request the break. Use hand-over-hand to manually prompt the break if needed (ignoring any challenging behavior).

- As soon as the request is made, remove the work and give the student a break. Set a timer for the prescribed break time, give a warning before it is up, and then repeat.

- Go through this series several times for the work period and schedule at least 1-2 work periods per day to practice. The more you practice, the faster they learn the skill and the more you can move on.

Embedding Work

Once the student is independently requesting the break AND the challenging behaviors have decreased, then you can start asking the student to tolerate very short periods of whatever they are escaping from. So, using the writing example, it might be writing one letter. When you do this the challenging behaviors will come back. A couple of caveats for handling those situations.

- Don’t let the student escape just because of the challenging behavior. Prompt him/her through the amount of work that you required (e.g., writing one letter). Then release him/her from the task.

- The student doesn’t have to ask for a break a second time. He asked the first time; you asked him to do 1 thing; after he does it (even though you prompted him), he gets the break. This teaches him that the contingency is still place and the communication response still works just with an added demand.

- If the student does what you asked without challenging behaviors, don’t push it and try to get more. You told him 1 letter, he gets a break after 1 letter is written. This just means that next time or the time after that, you can ask him to do a bit more.

- Once the challenging behaviors are not occurring for the small amount of exposure to the antecedent, then you can increase just a little more (e.g., write 2 letters). Be careful not to increase too fast. If you see behaviors increasing, you are going too fast. Drop back to a lower demand until they are better. If the student stops asking for a break, drop back the same way.

If you are thinking about teaching a student to request a break or to chill now or in the future, you can download the teaching protocol that has more details about the teaching process HERE. There are other ways, that we have talked about in previous posts, to address challenging behaviors that function to escape from situations. Some of these (like changing task demands) we might use in conjunction with teaching a break. However, teaching the break response, while one of the more complex, time-consuming strategies, is one that can last a lifetime and help the student be more independent in the future.