IEP Mastery Criteria: 9 Things You Need to Know

IEP mastery criteria is the unsung hero (or dastardly villain) in IEP writing. We don’t think about it nearly as much as we probably should. And there are so many ways it can help us or hurt us down the road as we actually are trying to teach the skills from the IEP.

We tend to slap on 80% or 4/5 on the end of the goal call it done. But, the mastery level can be one of the biggest area of disagreement when determination of mastery of the goals comes about because they are often written in a way that meant different things to different participants.

Why is IEP Mastery Criteria Important?

While IEP mastery criteria seems pretty straightforward, it can trip up an IEP team in many different ways. If it isn’t clear, there may be disagreement among the team about when the skill is or isn’t mastered. If the mastery criteria is written vaguely, there is unlikely to be agreement. And some mastery criteria can seem different depending on the reader.

And, IEP mastery criteria is critical when you go to create your system of data collection. There is nothing worse than sitting down to analyze your data, only to discover it doesn’t match the way the mastery criteria was written.

9 Tips for Practical IEP Mastery Criteria

So, I thought I would share a couple of things I’ve learned over the years that might help when determining mastery criteria. Here are 9 things to think about when you write that ending on the goal or objective. So let’s get started.

Looking for more support in writing IEPs?

Come get a free trial in the Special Educator Academy where we have workshops and study groups on them.

Join Us!

Come get a free trial in the Special Educator Academy where we have workshops and study groups on them.

1. Type of Skill

The first consideration in IEP mastery criteria is the type of skill the goal is addressing. Different skills lend themselves to different types of mastery. And even within the subject or area of the skill, you could have different needs for mastery.

Let’s look at reading, math and behavior as examples.

Reading

For instance, reading lends itself to accuracy of comprehension at different grade levels. But it also needs to focus on fluency of words per minute, and accuracy of words read. So depending on the focus of the goal, you could be writing percent accuracy (e.g., percent of comprehension questions correct). Or you could be writing mastery as x words/ minute in a second grade paragraph.

Math

Math lends itself to accuracy (e.g., 90% correct) in most situations. But sometimes we need to think about fluency (e.g., x problems per minute) with math facts.

Challenging Behavior

Challenging behavior is often measured by frequency of behavior over time (e.g., no more than 1 instance of hitting adults per week). However, if I was measuring crying, I might need to have mastery as duration. Because crying for 60 minutes one time a day (i.e., frequency=1) is more significant than crying 10 minutes each time for 3 times a day (i.e., frequency=3). And if the problem was the severity of the behavior, we would need different measures like rating scales.

2. Importance of the Skill

In addition to the type of skill, you have to choose how high you set your IEP mastery criteria based on how important mastery of the skill is to the student. We need to think about the importance of the skill to later learning and to safety and well-being.

Foundational Skills

Is it a basic skill that is foundational to later skills? For instance, reading decoding, fluency and comprehension are both pivotal skills in being able to read for knowledge later. We all know about the shift from learning to read to reading to learn. Because of that, early reading goals that focus on basic reading skills need to have higher levels of mastery. Mastering decoding at 60% is going to be problematic as the student’s independent reading becomes a foundation for learning new material.

Safety and Well-Being

Is it a skill that involves safety or well-being? Skills that are written for safety or that have safety involved in them are going to require higher levels of mastery.

For instance, crossing the street needs to be mastered at 100%. If a student masters it at 80%, he has a 20% chance of being hit by a car.

Let’s say we are writing a goal for lab safety in chemistry. It’s important for the student to demonstrate good use of precautions like wearing safety goggles and keeping hands clear of the bunsen burner when it’s tuned on. Those are goals that need to be at least 90% or 100% correct.

3. Age-Relevant Mastery Criteria

You also have to set your IEP mastery criteria based on whether it’s meaningful for the student’s age. For instance, saying that a student will be on-task in a group situation 100% of the time is probably not realistic for most ages. We all are distracted at times.

Similarly, if a typical peer responds to questions with correct answers 70% of the time, it is not reasonable for a child with an IEP to do it at 90%. Pay attention to how often behaviors occur in the typical students and use that as your guide.

4. How You Will Measure the Skill

Educators often lock themselves into a really complex data system, because of how the IEP goal is written. Think about how you will measure the skill BEFORE you write the goal or you will regret it.

Here is one of the best examples I’ve found (and done).

Problem

- You are writing a goal to focus on a student improving initiating communication or social interaction.

- You write a goal that he will initiate a social interaction with a peer on 4/5 opportunities.

- When you go to collect data on this, you realize that you don’t know what an opportunity to initiate a social interaction that he didn’t take looks like.

Solution

First, figure out your baseline of how many times he currently initiates during an activity like recess. Let’s say it’s between 1 and 2 times in a 15-minute recess time).

Then, write the goal as:

Stew Dent will initiate an interaction with a peer at recess 3 times during a 15-minute period.

This way you only need to count the number of times he initiates and not how many “opportunities” he has (that you can’t determine anyway). It streamlines your data and makes it more meaningful.

Conditions of Measurement

In addition to writing the goal to fit what you can actually observe, make sure that you are writing in conditions of data collection. For instance, sometimes it’s not feasible or reliable to take data throughout the entire day. For instance, counting every verbalization a student makes throughout the day is going to be difficult in a classroom. But worse, trying to do it may result in unreliable (and inaccurate) data. There are too many distractions.

So, to address that, we might plan to take samples of data. But, if you are planning to assess the skill by taking a weekly sample or probe data, indicate that in your level of mastery.

For instance, if you write that he will do it 4/5 days, you are going to have to take data every day. So you might want to write it as he will demonstrate the skill on 4/5 opportunities on twice weekly samples collected over a period of 3 weeks. Then you take a sample twice a week and use that data.

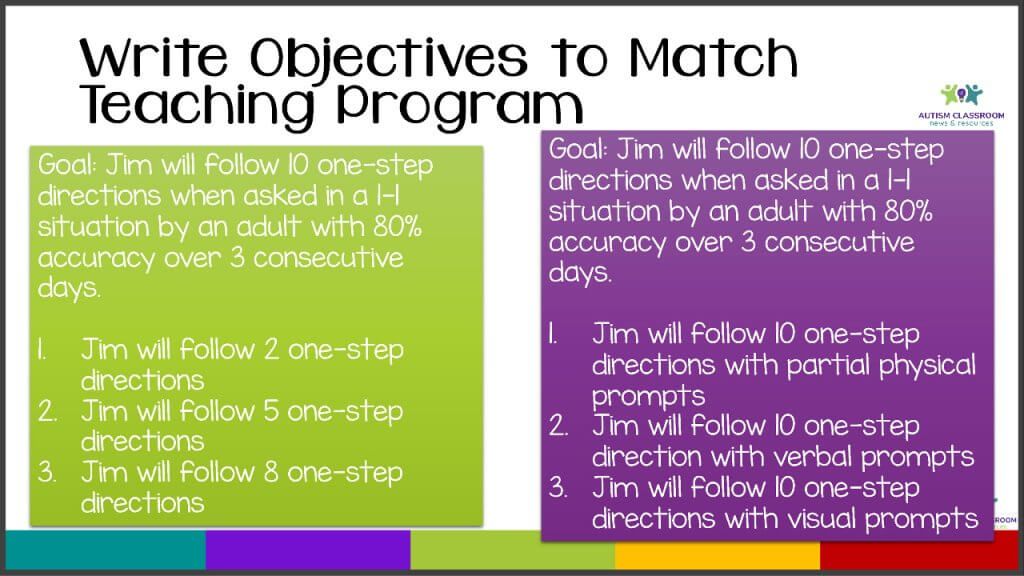

5. Instructional Steps

This is one that I learned most recently. You want to make sure that you are thinking about your instructional steps–the order in which you are going to teach the skill before you write the goal.

For example, I am teaching one-step directions by introducing 1 direction, then a second direction and then randomizing them. Then introducing a third direction and randomizing all of them.

If I write my objectives for a goal to teach 10 1-step directions as

- S. will follow 10 one-step directions with partial physical prompts on 8/10 opportunities.

- S. will follow 10 one-step directions with gestural prompts on 8/10 opportunities.

- S. will follow 10 one-step directions with visual prompts on 8/10 opportunities.

But then I am teaching it by introducing 1 direction to mastery. Then another. And then randomizing them. By the time I need to report progress on objective #1, I may have only introduced 2-3 directions. So I have to test the student on directions that haven’t even been introduced.

But if I wrote the goal with objectives like this:

- GOAL: S. will follow 10 one-step directions independently on 8/10 opportunities.

- S. will follow 2 one-step directions independently on 9/10 opportunities.

- S. will follow 5 one-step directions independently on 9/10 opportunities.

- S. will follow 8 one-step directions independently on 9/10 opportunities.

Then I don’t run into issues with it clashing with the way I’m going to teach the skill.

6. Practicality

Next, make sure to write your goals and objects so they are practical to measure. For instance, if you have a student working on walking independently, use the criteria as something like, “John will walk to the bathroom from his work station independently.” This is going to be much easier to implement than “John will ambulate for 25 feet independently.”

Please don’t make me measure the distance to see whether the skill was just demonstrated. Pick practical elements of the environment that you can use to measure and build them into the criteria.

7. Include a Time Frame for IEP Mastery Criteria

Finally, you want to make sure that you are including a time frame in your mastery criteria. Here’s why.

I once was working with a student and he was making great progress. But when we sat down with the parent for a quarterly meeting, the teacher was presenting the data on the goals. But she averaged all the data for the 9 weeks together. Consequently, she was averaging his performance when we started teaching the skill with his performance at the end when he had “met mastery criteria” – at least in my eyes.

Essentially she was averaging the pre-test with the post test. The averaging washed out his performance increases. I explained all this. And the teacher got it. But, Mom insisted that it had to be an average of all the data across the IEP because of the way we had written the goals (without a time frame).

So, now I write goals and objectives in this manner.

Jimmy will follow a 1-step direction presented in a small group independently on 90% of the trials over a 2-week period.

This goal tells us that we are going to use the data from a 2-week period and he needs to independently follow the direction on 90% off the opportunities when accumulated over a 2-week period. I don’t need 9 weeks of data. The 2-week period just keeps rolling until mastery is achieved. This also assures that the mastery of the skill wasn’t a 1-time thing and that the student is likely to maintain the skill longer.

8. Make Mastery Criteria Meaningful

We need to make sure that our mastery levels mean something. Let’s assume that you expect that a student will not be able to master a skill at 75%. And you have determined that typical students would display the skill at that level. In this situation, then, I strongly suggest that reduce the skill (i.e., change to an easier skill) rather than the mastery.

Mastering something at 50% is not really meaningful; it’s hit or miss. So instead, add prompts or have them master a subset of steps of the skill rather than lessening the level of mastery. Change the goal instead.

Sometimes I will do this if a team member is really focused on keeping a goal in the IEP. However, most of the time I would rather make the goal easier and master it more strongly so we can move on to more advanced skills.

9. Discuss Mastery With the Team

Finally, it’s always a good idea to have a discussion with the IEP team about the mastery criteria. It will help to have those discussions early on so you don’t run into the issue I did in #7. Similarly, you don’t always know how interpretable things are until you get feedback from others. And you want to make sure that all the team members believe that the goal is appropriately challenging but attainable.

I would love to hear your thoughts and questions about writing IEP goals…so if you are an educator, hop over to the SpecialEducatorConnection Facebook group and share or ask to join. Make sure to answer the questions so we can let you join.