Welcome back to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast. I am Chris Reeve and I’m your host, and I want to start with a story. So, and it’s not a bad joke, but it sounds like that way I’m going to start it. I walked into a preschool classroom one day and the preschool teacher said,

I’m so glad you’re here. I’ve realized I need your help with this kid. And I realized that for this kid, it’s all about choices.

Now, this preschool teacher and I had worked together for a good time by then, and for this particular kid and many others that I’ve known over my time, he liked to be in control of everything. And he did it by refusing to follow the teacher’s directions. He told you what he would do other than what you had just told him to do. And he would tell other people, kids and adults what to do. We also found that we were always getting into power struggles with him. He could suck you into a power struggle faster than my money disappears at the Target Dollar Spot.

Have You Met This Kid?

I’m guessing some of you may have met this kid because I know he’s not the only one. How in the world do we address what we consider to be defiance and noncompliance and that type of behavior, when we know that the kid just wants to run things? He wants to be in control, it might be that he wants to be the center of attention. So the function of the behavior is to gain attention or he wants to avoid doing work. Maybe it’s an escape-related problem. It’s the fact that he meets those needs by what appears to us to be controlling the situation.

I’ve also had students for whom being in charge is a setting event for challenging behavior. And if you haven’t heard of those before, I’ll put a link to the podcast where I talked about setting events. Essentially, if someone argued with him and prevented him from doing or getting what he wanted earlier in the day, then the challenging behavior would crop up later in the day. And the trick that worked for him was to make him think that he was in control while we got what we needed. And an easy way to do that is give him choices so that he thinks that he’s in charge.

In Episode 54

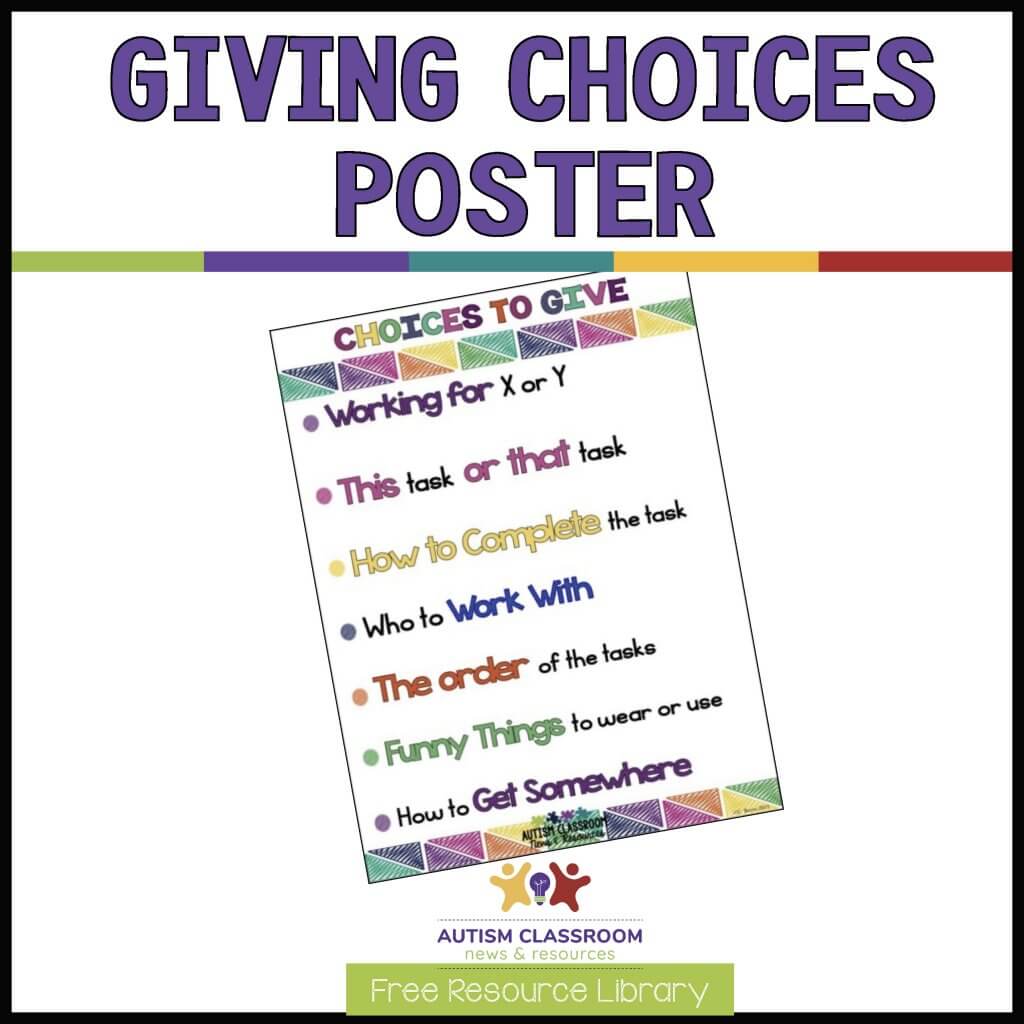

So I’m going to talk about choices today, why they make sense and how we can use them effectively because they aren’t the solution to every problem and we can do them wrong. I also have a free download for you in the blog post that this goes with. So in this post and you will find a visual reminders poster, and you can also get a link to my 30 behavior support videos that are in our resource library. Some of which deal with this topic as well.

So let’s get started.

Why Choices?

Giving choices is one of the preventive behavioral strategies I recommend in almost every behavior support plan. Many of our students with challenging behavior are reinforced by reactions to their behavior. Think about a teacher who can’t present a lesson because the student is possibly hurting someone else (possible escape-related behavior), or the student whose behavior is the center of attention as a class clown (possible attention-seeking behavior). Both functions are reinforced by the student getting an expected outcome that reinforces the behavior. Choices increase the likelihood that a student will engage with the task itself.

We All Want Choices

Most people do not like being told what to do. Why should we expect it to be different for our students? Being asked to do something is always preferable to being told. Hence, my mother used to ASK me, “Do you want to take out the garbage?” Um, no I don’t WANT to, but I will. This is the reason it’s so hard for us to remember in the classroom that we want to give directions clearly–and not as choices. Because the student I talked about at the beginning of this post….he would say, “NO!” and refuse.

What the Research Says

Dunlap, Kern-Dunlap, Clarke & Robinson (1991) found that giving choices of which science assignment to do resulted in lower challenging behavior and higher on-task behavior for a student with developmental disabilities. Similarly, when students with emotional disabilities were given choices of activities in curriculum, they demonstrated more on-task behavior and less disruptive behavior (Dunlap, dePerczel, Clarke, Wilson, Wright, White, & Gomez, 1994). And they even found that this effect held when the students had preferred items in the no-choice activities. This indicates something about the opportunity to make a choice (rather than just having preferred activities) plays a role in improving behavior.

There is also research that found that choices of consequences (e.g., reinforcers) for task completion was favored over choices of the tasks themselves by preschoolers (Fenerty & Tiger, 2010). This may be related to how it impacts the preference for the reinforcer at that moment in time. However, as with most things, it may vary by student (Vaughn & Horner, 1997).

Common Types of Choices

Types of choices can vary and it depends on the student. However, some common choice types might include choosing:

How to Give Choices

We know some students really can benefit from being given choices of reinforcers, tasks, or how tasks are completed. But how do we do that and still get our work done? I’ve found these tips helpful in setting students (and staff) up for success with choices.

1. Choices Need to be Reasonable

Obviously don’t give choices that aren’t available. For instance, “Do you want to do your math worksheet or do you want to go to Disney World?” is not a reasonable choice. But you could give a choice of “Do you want to do Worksheet A or Worksheet B?” Choose choices that are going to get your needs met but the student gets to participate in the decision. This way you get the work done you want, but he gets to “buy into” getting it done. In a very nonbehavioral way, think of it as “saving face.” He gets to look like he was in control, when really YOU were in control.

2. Pair with Visuals

You can use the objects / items you are giving choices about, demonstrate the action you are letting him choose, or use visuals. Either way, if the student has difficulty understanding language, giving a visual or object support to the choice can make it more concrete.

3. Write a Visual for Staff

It’s hard to come up with choices sometimes in the midst of giving directions. So make a list of common choices you might use for students and post it in the classroom. This way all the staff can reference it to give choices more often.

4. Avoiding a Punishment Isn’t a Real Choice

Choices should be between options that you want the student to choose. Presenting an option to a student of doing a task or getting punished is not really giving a choice. It’s threatening what will happen if the student disobeys. That’s not a proactive behavior management strategy. Similarly, “you have to do this or I will help you”–meaning I will make you is not a choice. And along the same line, “Walk to class or I will carry you” also not a proactive choice….and you may find that carrying them reinforces the challenging behavior.

5. Mix Them Up

Don’t always give the same choices over and over–it’s boring for both of you. Instead make the list from #3 as a way to help everybody mix it up. New and novel choices can work as motivators just because they are different.

6. State Them Clearly

Remember that a choice is not whether to do something you need the student to do, or not. Generally you should state choices matter of factly and don’t negotiate them (unless your FBA indicates that is the best course of action). Otherwise you are back in the power struggle you are trying to avoid. Instead say something like, “It’s time for us to do math. Do you want to do it with Ms. X or with me?” Or say, “It’s time for music. Should the class sing “Down by the Bay” or “Freeze” as the first song when we get there?” The question is the choice, not the task.

So, for some of your students, like the one I started talking about at the beginning of this post, your day may be filled with choices. But isn’t it better to fill the day with choices for as many activities as possible than to constantly be redirecting, punishing, and telling a student what to do?

How to Give Choices

We know some students really can benefit from being given choices of reinforcers, tasks, or how tasks are completed. But how do we do that and still get our work done? I’ve found these tips helpful in setting students (and staff) up for success with choices.

1. Choices Need to be Reasonable

Obviously don’t give choices that aren’t available. For instance, “Do you want to do your math worksheet or do you want to go to Disney World?” is not a reasonable choice. But you could give a choice of “Do you want to do Worksheet A or Worksheet B?” Choose choices that are going to get your needs met but the student gets to participate in the decision. This way you get the work done you want, but he gets to “buy into” getting it done. In a very nonbehavioral way, think of it as “saving face.” He gets to look like he was in control, when really YOU were in control.

2. Pair with Visuals

You can use the objects / items you are giving choices about, demonstrate the action you are letting him choose, or use visuals. Either way, if the student has difficulty understanding language, giving a visual or object support to the choice can make it more concrete.

3. Write a Visual for Staff

It’s hard to come up with choices sometimes in the midst of giving directions. So make a list of common choices you might use for students and post it in the classroom. This way all the staff can reference it to give choices more often.

4. Avoiding a Punishment Isn’t a Real Choice

Choices should be between options that you want the student to choose. Presenting an option to a student of doing a task or getting punished is not really giving a choice. It’s threatening what will happen if the student disobeys. That’s not a proactive behavior management strategy. Similarly, “you have to do this or I will help you”–meaning I will make you is not a choice. And along the same line, “Walk to class or I will carry you” also not a proactive choice….and you may find that carrying them reinforces the challenging behavior.

5. Mix Them Up

Don’t always give the same choices over and over–it’s boring for both of you. Instead make the list from #3 as a way to help everybody mix it up. New and novel choices can work as motivators just because they are different.

6. State Them Clearly

Remember that a choice is not whether to do something you need the student to do, or not. Generally you should state choices matter of factly and don’t negotiate them (unless your FBA indicates that is the best course of action). Otherwise you are back in the power struggle you are trying to avoid. Instead say something like, “It’s time for us to do math. Do you want to do it with Ms. X or with me?” Or say, “It’s time for music. Should the class sing “Down by the Bay” or “Freeze” as the first song when we get there?” The question is the choice, not the task.

So, for some of your students, like the one I started talking about at the beginning of this post, your day may be filled with choices. But isn’t it better to fill the day with choices for as many activities as possible than to constantly be redirecting, punishing, and telling a student what to do?