Welcome to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast, the podcast for special educators who are looking for personal and professional development. I’m your host, Dr. Christine Reeve for more than 20 years, I’ve worn lots of hats in special education, but my real love is helping special educators. Like you. This podcast will give you tips and ways to implement research-based practices in a practical way in your classroom to make your job easier and more effective.

Welcome back to the Autism Classroom Resources Podcast. I’m Christine Reeve, and I’m your host. And I’m going to start with some examples this week.

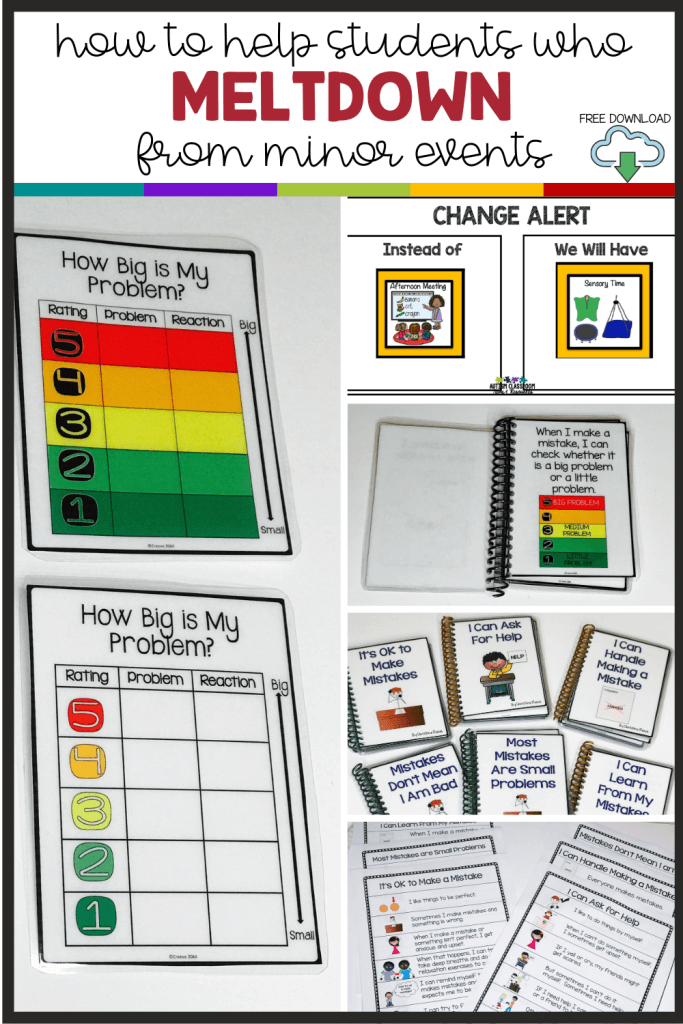

Examples of Catastrophic Reactions to Changes and Minor Events

Brett was a student who had a meltdown in the classroom seemingly out of the blue one day. Turns out he was extremely upset because another student was absent. He never played with or interacted much with the other student. But he was upset because there was one less student in the classroom. Not having that child checking in on the Who’s Here board ended up tanking his whole day. And it took us half the day to realize what the problem even was.

Deandre was working quietly on his math at his desk when suddenly he started tearing at his paper with his eraser, ripped up his paper, got up and threw it away. And then he sat down and started the assignment over. When his second grade teacher asked what happened, he said he made a mistake.

Amanda seemed happy as could be when she walked into the classroom on Tuesday morning. But she started screaming when she got to morning meeting. Turns out she was upset because the teacher was taking some time to plan in the classroom while the aide was running morning meeting that day. The teacher usually ran morning meeting. Amanda took most of the morning to recover from the upset of having a different person run the morning meeting.

And then there is Kai who had an amazing day at school only to have it fall apart at the end. Kai’s mom got stuck in traffic and was 5 minutes late to pick him up. And his day ended in a tantrum in which we had to carry him to the car.

Episode 66

Do any of these students sound familiar to you? They are all conglomerates of students I have met over the years. But they are all very real and all very typical of many of the students, particularly those with in general education, with ASD.

And their reactions and how we can help them are what I want to talk about this week. Plus, I have a freebie for you in the blog post and you can find that and a transcript and some examples of the strategies below.

And if you are looking for more ideas for addressing challenging behavior in your classroom, you may want to check out the free webinar on Preventing Challenging Behavior. Of course we have a whole course on Behavioral Problem Solving the Special Educator Academy as well, so come try a free 7-day trial at specialeducatoracademy.com.

Now, let’s get started.

Strategies to Help Students with ASD Manage Reactions to Common Changes or Events

In last week’s episode (episode 65), I talked about students with ASD who overreact to the smallest of events, often involving change or small problems. I typically call it catastrophic reactions to trivial events. Often these students melt down, but sometimes they also shutdown or give up. The significance is that they overreact to events that are not in line with their reaction.

Each one of these cases was an example of an overreaction to something that was not a big deal. But to the student, it clearly felt like a big deal. And they didn’t know how to handle it. So in this week’s episode I’m talking about how we can help those students to regulate their reactions to those events in life that seem trivial to us, but feel like the end of the world to them.

It’s important to recognize that these are events that we might be seeing more of when there are events in the students lives that are increasing overall anxiety…like Covid 19 and changes in schooling. At those times, we may see more difficulty with problems with problems that seem even more trivial.

In the best of all possible worlds, we would expect changes that would upset students and prepare for them. This doesn’t always mean that we would not have the change. Because after all, our students have to learn how to tolerate change to live in this world. If 2020 taught us nothing, I think we have all learned that. But, we can teach our students to handle change if we know a change will be a problem.

Use Visual Schedules

Sometimes we can prepare the student right before a change occurs, if we know about it beforehand. For instance, if we know there is going to be a change in the schedule, we can give them a heads up.

One way to do that is to make sure that the student’s schedule reflects the change. That might mean just sending an adult over to change out the visuals on the student’s schedule with the new event. Or event to change it when he is at the schedule and tell him about the change. It’s important to remember that you can use visual schedules to teach students to be more flexible and you can learn more about that in this post.

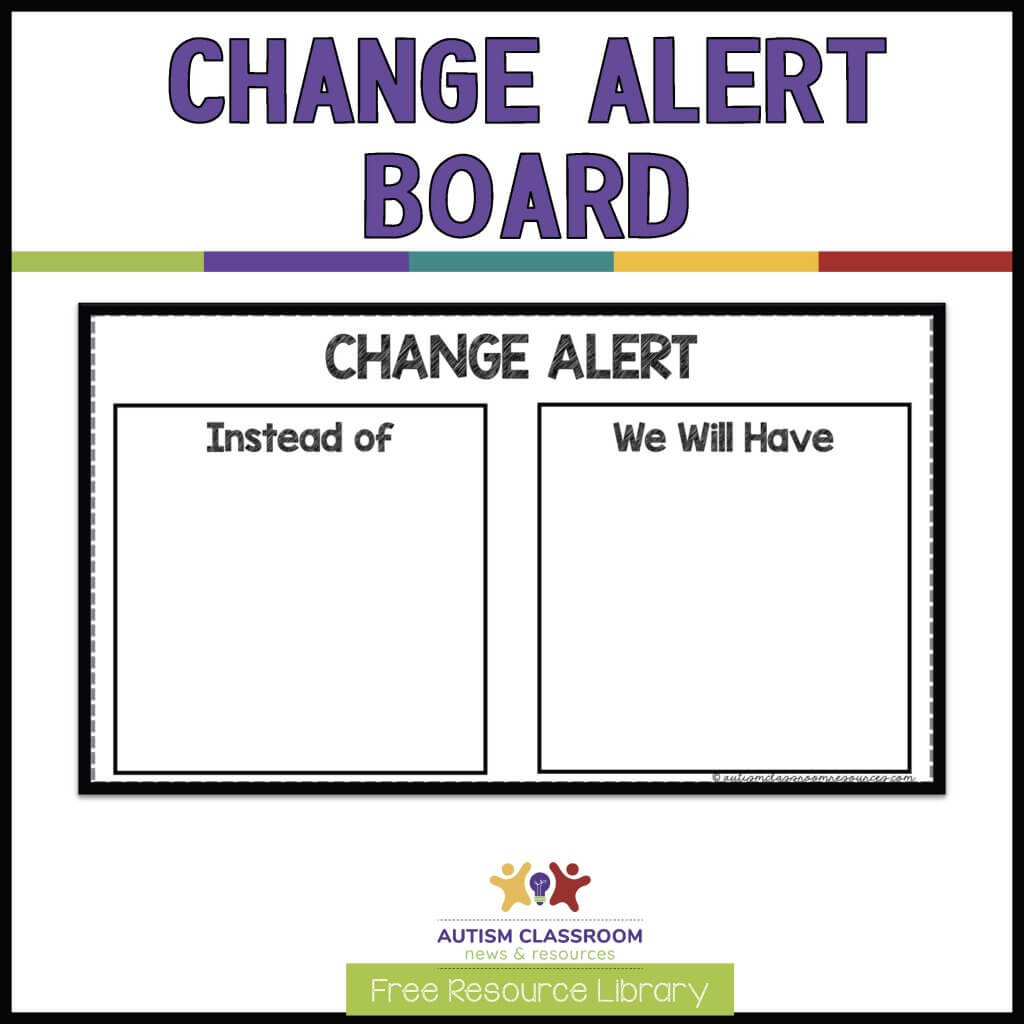

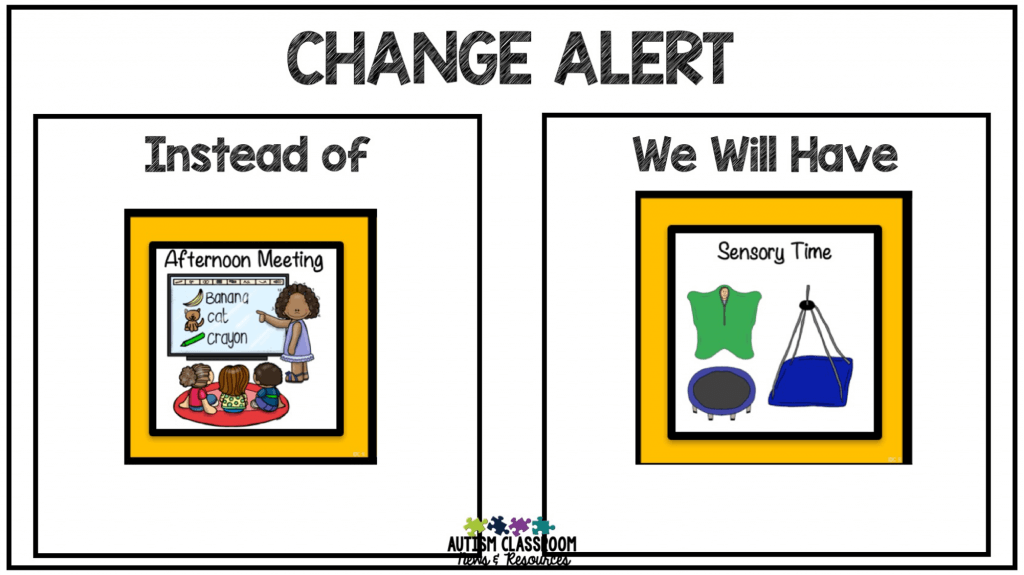

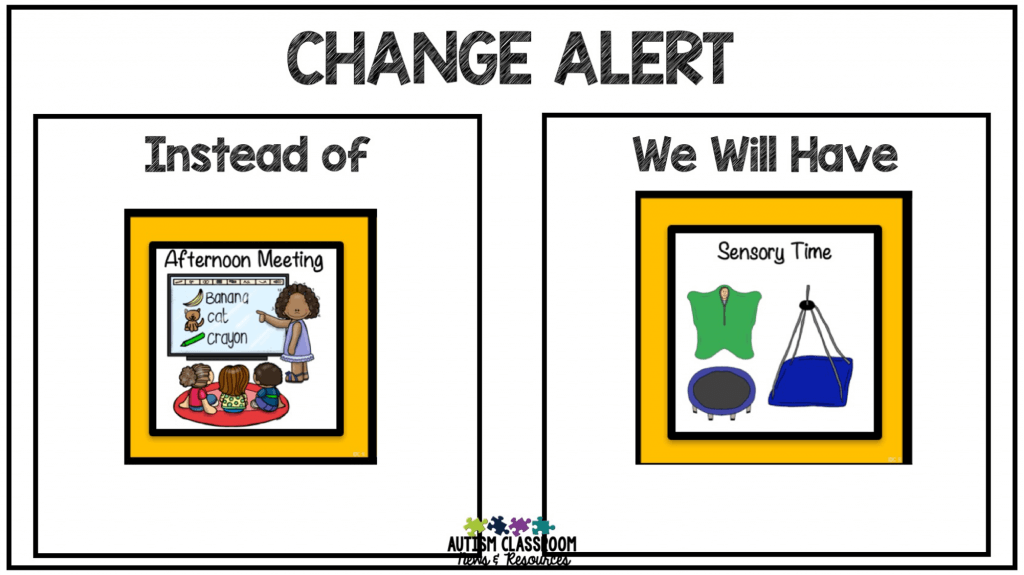

Use Change Boards or Notes

Another way is to use a Change Board. A change board can be used to show a change in the classroom schedule. I use it for students on picture schedules so it shows what was originally scheduled and then what it was changed to. You can grab a free Change Board in the Resource Library below.

Similarly you could use a a note for students who can read. It might say, Speech will be changed today because Ms. Rosemary has a meeting. The new time is 2 p.m. this afternoon.

We could use a similar strategy for changes in staff or substitutes. Or for changes to who will be running different activities. So for instance, for Amanda, who was upset because a different person ran morning meeting, a change board to let her know ahead of time might have given some time for her to adjust. If that wasn’t enough time for her to adapt, some of the next strategies might be helpful.

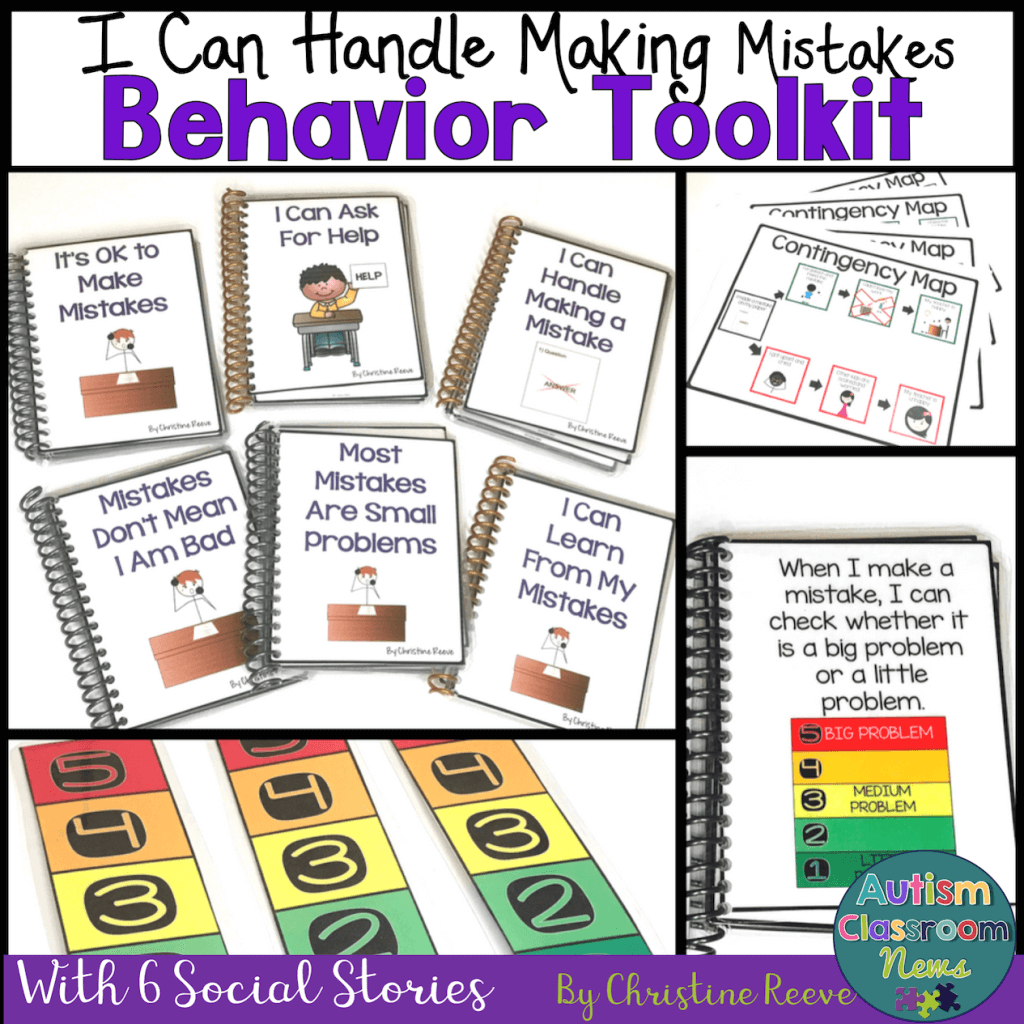

Use Social Narratives

Social narratives, sometimes referred to as Social Stories, are a way of helping students know what to expect about upcoming situations, the perspectives of those around them, the social expectations of others, and more. Social narratives can be helpful in helping students learn to manage situations that might trigger catastrophic situations.

For instance, if we know that Kai gets upset whenever he might have to wait for someone who is late, we can write a social narrative about what it means to wait when someone is late, why someone might be running late and how it eventually will probably work out OK. We can also include coping strategies of things to do while waiting for someone to pick him up. And coping strategies about how to stay calm. Then we can read that social narrative before it’s time for dismissal and before the event happens. And we can practice the coping strategies while waiting to stay calm.

For Deandre, who got upset because he made a mistake, we might have a social story talking about how writing the wrong number down is just a small mistake. And the social narrative could share strategies for fixing the mistake calmly and quietly so that he can continue working.

The great thing about social narratives is that, while they are typically best used in concert with other tools, they are good at introducing strategies that can be used and concepts to be taught. And they are helpful in allowing students to sometimes see a different perspective on a problem.

Teach Self-Regulation Visually

There are tons of ways you can teach students to self-regulate, and I’ll talk a bit more about them in future episodes. But the one that stands out here as being most helpful is a 5-point scale focusing on whether it’s a big problem or a small problem. Sometimes we call this a Size of the Problem Scale. This can be a useful tool for students who overreact to the problem and make a big problem out of a small problem. So this is a good teaching tool for these students to learn over time and help them learn to stop and think to self-regulate their reaction.

For instance, this might be a good strategy for Brett (or Deandre) to work on when thinking about the issue that upset them. It would be a good strategy for when they first started to get upset or after they de-escalated to look back and debrief about the problem.

Summing Up

In reality, we would use a combination of these strategies in most situations. For Brett, for example, after we learned that students being absent was a problem, we created a social narrative about that issue. We reviewed it at times when he was calm. Then we talked about it in the context of big and small problems and pointed him to the scale to when we talked about it. We then used that scale the next time someone was absent to practice. If we knew someone would be absent, we could give him a heads up with a change board or a visual.

As with any type of behavioral support, it’s a combination of prevention strategies and longer-term teaching strategies. But once we have an understanding of the reactions and the events that trigger them, we can start to help students understand and learn how to manage those reactions.

To help with that, if you have a student who struggles with making mistake, like Deandre in the illustration above, you might like my I Can Handle Making Mistakes Toolkit designed for students just like him. And make sure that you grab your free Change Board below from the Free Resource Library below.

I’d love to hear your thoughts about working with these types of students. If you are an educator, hop over to our free Facebook group at specialeducatorsconnection.com and share. In the meantime, I’ll be back next week with a new episode. Thanks for everything you do for your students.