In need of interventions for defiant behavior? Have you worked with a student who used negative behaviors to constantly draw you into a power struggle? Ever had a student who seemed to be able to find different ways to push exactly the buttons that upset you or someone else in your classroom? Or a student who wouldn’t back down when you gave him a direction he didn’t like?

Think about a student with non-compliant behavior who refuses a direction. You tell him to get his math done. He says, “No.” You tell him he will lose choice time, and he says, “Fine!” And you find yourself arguing with him and trying to think of what else you can do to get him to do the desired behavior. You feel like now that you’ve insisted, you have to follow through. So you find the argument and problematic behavior escalating until he may actually say, “I’m not going to and you can’t make me!” And let’s face it…you probably can’t.

Yep, I think we’ve all had that student that displays oppositional behavior towards authority figures and peers. Or more than one. And sometimes we (or others in our class) feel that they can’t back down or not impose a negative consequence once a power struggle starts. You’ll hear some behaviorists and teachers say, “you can’t give in to him.”

Power Struggles: What I’ve Learned

But here’s what I’ve learned after working with these students for many years (and reading the literature and clinical studies about them as well). It is possible to “win” a power struggle, but the price for winning these behavior problems isn’t always worth it.

Yes, you can hold your ground and possibly get the student to bow to your will. In some of our cultural discipline systems in the school setting, we think of this as gaining the student’s respect. But really all we are teaching him is that someone has power over him. We haven’t taught him to be more independent. We haven’t taught him to follow adult directions. We’ve taught him that he has to do what YOU say because you have power over him. These types of interventions for defiant behavior are probably not going to do much for his trust in you either.

More likely though, power struggles lead to the teacher “losing” and this student winning. And here’s why…you have other things to do and the student doesn’t. You have other students to attend to and teach and the student just needs to wait you out.

And when that happens, guess what? We make the problem worse. Yep, not only do we not get the student to do what we want….he’s actually more likely to do the same thing (only louder or more disruptive or even more aggressive) as last time.

Gerald Patterson was an amazing cognitive psychologist who did a lot of the early research in the development of conduct disorder. (Yes this is a blog about autism and special education, but the principles of behavior are the same regardless of your “diagnosis.”). One of the things that he noted in families with children eventually diagnosed with conduct disorder was what he called the coercive cycle. You can read a more descriptive version of the coercive process here, but I’ll give you a quick overview.

Coercive Cycle

- An adult gives a demand.

- The child refuses.

- The adult gives the demand louder or stresses it more.

- The child refuses and begins to “talk back.”

- The adult begins to yell at the child.

- The child continues to refuse and yells back.

- The adult begins to threaten the student (e.g., you better do this or you will be grounded)

- The child responds by threatening or yelling back or becoming aggressive.

- At this point the adult can’t hold out any longer and has nothing left in the toolbox to threaten with, and so he ends the interaction.

- The child then gets out of the situation.

- So next time, when the adult gives a direction, the child is more likely to start at the level of the escalation cycle that resulted in ending it—so he starts with yelling and possibly aggression when the direction is given. So this time when the cycle escalates, it gets more severe more quickly and so on.

Applying the Coercive Cycle

This pattern of escalation means that our power struggles aren’t just not teaching our students appropriate behaviors, they may be making it worse. Because again, your student has nothing to do except to wait you out but you have other things to do.

So all of this is why it’s so important to use these interventions for defiant behavior to PREVENT power struggles to avoid both the frustration (by both participants) and avoid the escalation. And there are strategies and effective interventions you can put in place when presenting directions that make it less of a “yes/no” situation. While they aren’t new, revolutionary strategies, they are tried and true and they work for exactly this type of situation.

5 Ways to Prevent Power Struggles in the Classroom

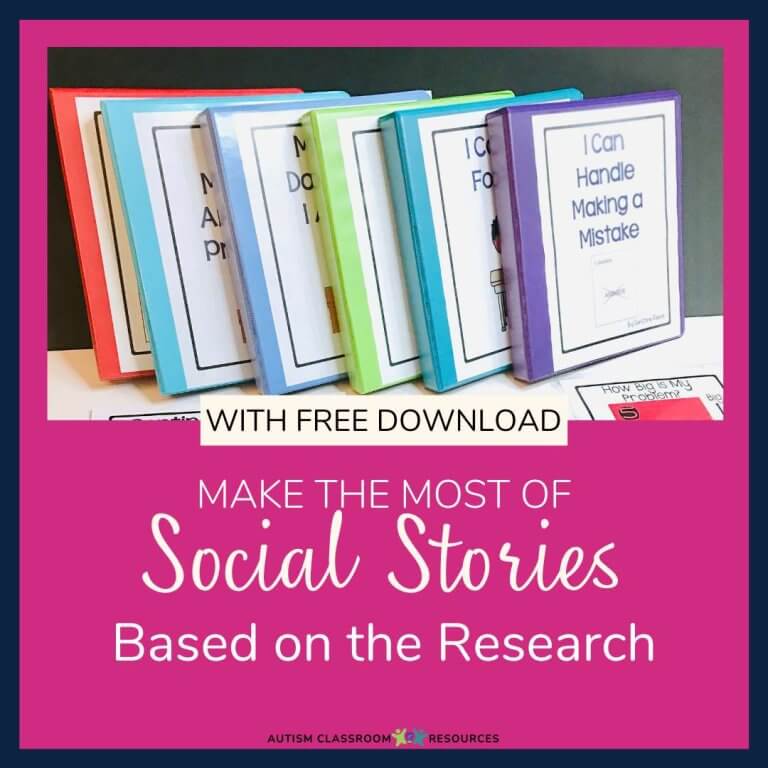

1. Use visuals

Visuals aren’t magic, as I noted in an earlier post. However, it is amazing how many times a simple symbol or sign or note will be more successful at getting someone to do something they don’t want to do. It’s something about not being able to argue with a visual. The visual doesn’t respond. So, whenever you can, give the student a schedule, or a list or even just a first-then visual as a great way of asking them to do what you want.

For tips on how to redirect with visuals, check out this video:

2. Giving Choices Can Prevent Power Struggles

Choices are another way to increase compliance and good behavior. And increasing compliance decreases power struggles. Clearly, the choice isn’t between going to Disney World or doing his math. But it could be whether he wants to work on money skills or counting first. Or if he wants to sit on the ball chair or a regular chair to do his math. To read more about using choices and other interventions for defiant behavior to gain compliance, check out this post.

Check out this video for tips on giving choices

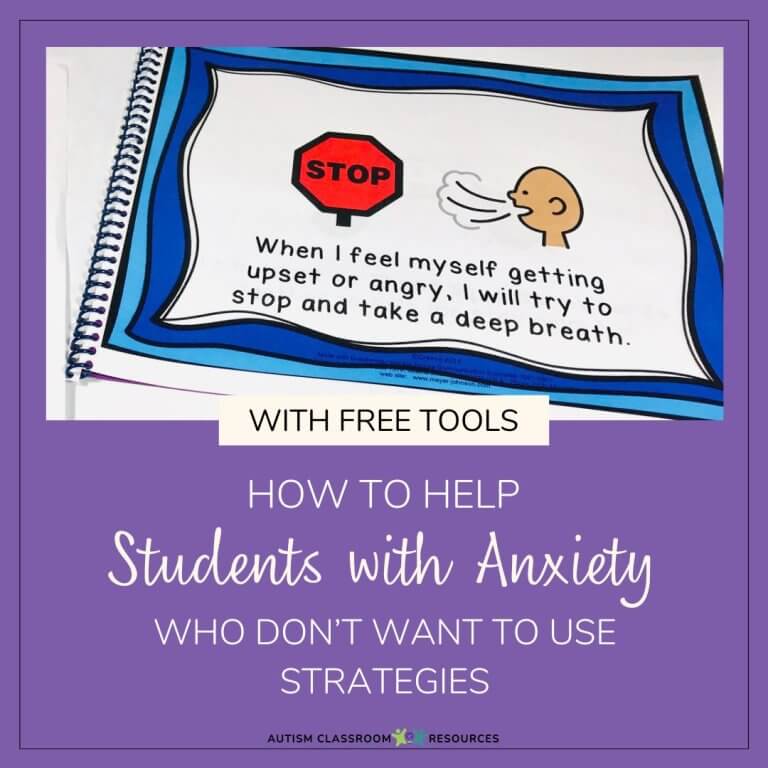

3. Offer Help to Avoid Power Struggles

I realize this sounds counterintuitive but this is an important component. You want the student to do something, so why would you offer to help him with it? Have we faced tasks we didn’t like in our own lives? Maybe it was a presentation you were scared to give in school. Or a doctor’s visit you were worried about. Did someone offer to be in the audience of your presentation or go to the dr. With you? And did that help you feel better? This works on that same principle. Knowing you are not alone can often help make a hard thing easier. Offering to help a student who needs extra behavioral support doesn’t have to mean that you do it for him or that you tell him how to do it. It means you might join in and do it alongside him. Or take turns. For instance, you might start off by reading a page of the reading assignment and then having him read a page. Or if it’s cleaning up, maybe you take turns putting things away. Gradually as he becomes more engaged, you can probably fade your presence out.

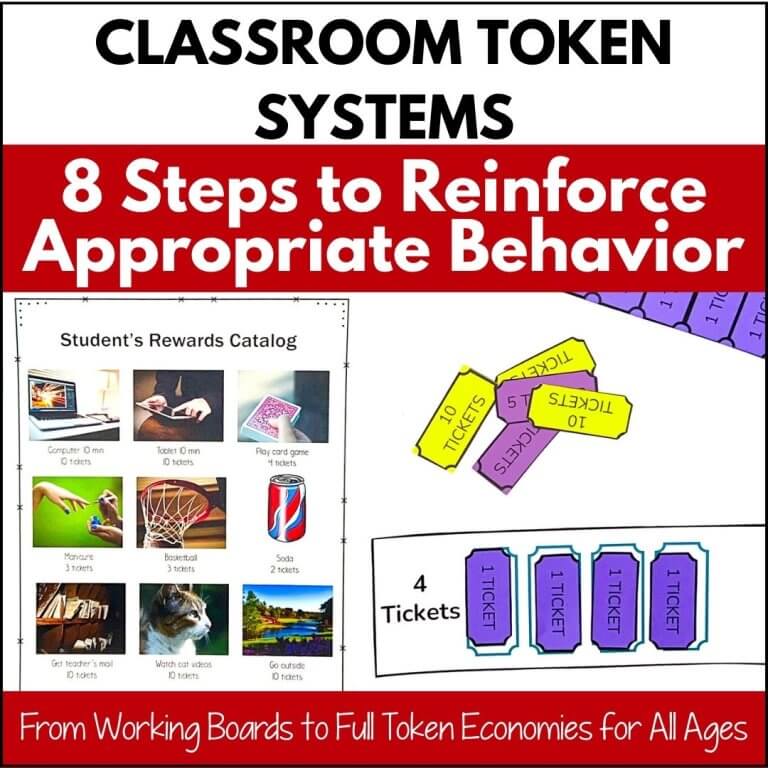

4. Use Positive Reinforcement Instead of Punishment

I know this is a theme I focus on in this blog because it builds skills instead of eliminating them. However, in this case, it has an even more practical reason to avoid punishment and negative attention. Typically punishment involves giving a penalty or removing the student from a situation or desired upcoming event. What if you take those things away and he still doesn’t comply? Then what will you do? We often threaten to remove things or place penalties on the student, but many times the noncompliance can be more reinforcing than the penalty is punishing. When that happens, we have to either escalate in the punishment or we run out of options. Positive reinforcement, on the other hand, allows us to reinforce when we see the behavior we want to see (to increase it) and just not reinforce when the behavior we want to decrease shows up. It gives us many more options. For tips on using reinforcement effectively, check out this post.

5. Don’t Engage During Power Struggles

Finally, the most important way to avoid power struggles is simply not to engage in them. I have worked with students who I have declared that they know how to suck you in. They know how to get you engaged in a power struggle…that you won’t win. Working with students shouldn’t be about winning or losing for the adult. It should be about whether the student is learning. If you are arguing with him instead of using these preventative interventions for defiant behavior, he is not learning. Visuals can be an effective way of doing this because you can leave them with him and walk away. You will know he’s been given directions but you won’t be there to argue with him. Sometimes just being left on his own will make it likely that he will go ahead and complete the task.

[socialpug_tweet tweet=”Sometimes teachers feel challenged by students who don’t immediately comply. And it’s easy to engage in a power struggle. But sometimes we need to step back and reassess. Find 5 ways to avoid power struggles in this post. #pbis” display_tweet=”Sometimes teachers feel challenged by students who don’t immediately comply. And it’s easy to engage in a power struggle. But sometimes we need to step back and reassess.” style=”2″]

Granted these tips and behavioral interventions for defiant behavior won’t work every single time. But at the very least they will keep you from being sucked into the power struggle and wasting your time with these problem behaviors. And often it will result in the student actually doing the target behaviors.

Yes, there are times when winning a power struggle is important to maintain discipline. But you want to choose to hold your ground in those situations when you have time and energy to see it through and when the outcome is important.

Looking for more ideas and new ways of handling disruptive behaviors? Join us in the Special Educator Academy for a whole course on Behavioral Problem Solving.

Like the Videos in This Post? Get 28 More in the Free Resource Library!

Come join the Academy and check out the Behavior course. Grab a free 7-day free trial with the button below.