If you’ve worked in autism or special education, you’ve likely heard of social stories. Sometimes called social narratives, social stories have been widely used since the 1990s to help students understand specific situations, navigate social expectations, and develop coping strategies.

INSIDE: This post covers a clear picture of what social stories are, along with how to use them. It provides a definition of social stories, sometimes called social narratives and reviews Carol Gray’s recommended components.

The post then covers the research on the effectiveness of social stories with suggestions of how to best use them as an evidence-based practice. Finally it shares how they can be used effectively, based on the research, in a real classroom. Free and commercial social stories are offered for teachers to try in their classrooms.

Table of Contents

But here’s the thing—social narratives aren’t a magic fix. Some people think that simply reading a social story to a student will change their behavior, but that’s not how they work. When used correctly, they can be a valuable tool, but they need to be structured thoughtfully and used in the right situations.

Let’s break down what social stories are, how they should be written, and what research says about their effectiveness.

What Are Social Stories?

Social stories were developed by Carol Gray in the 1990s. They are individualized stories designed to describe a situation from the student’s perspective.

They aren’t just meant to tell a student what to do. Instead, they provide information about:

- Where and why the situation occurs.

- How others feel and react in that situation.

- What the student can do to navigate the situation successfully.

Because individuals with autism often have difficulty understanding others’ perspectives, social stories can help them process different viewpoints and expectations.

An Example of a Social Narrative

Here’s a simple example of a social story about waiting quietly:

“I go to kindergarten in Mrs. R’s classroom. Sometimes in school, I have to wait for the other children to finish their work before we do the next activity. Sometimes waiting is hard for me.

When I talk to myself, other kids can’t hear the teacher or do their work. My teachers want me to be quiet while waiting. When I feel like talking, I can ask Miss N for a toy to hold, or I can just talk to her.

If I’m quiet while waiting, I earn a token. When I earn enough tokens, I can pick a fun activity. My teachers will be very proud of me if I can be quiet.”

Carol Gray’s Components of a Social Story

Carol Gray’s model includes several types of sentences that help structure an effective social story:

- Descriptive Sentences – Explain where, when, and why the situation happens. (e.g., “Sometimes in school, I have to wait for the other children to finish their work before we do the next activity.”)

- Perspective Sentences – Describe how other people feel or react. (e.g., “When I talk to myself, other kids can’t hear the teacher or do their work.”)

- Affirmative Sentences – Reinforce why the skill is important. (e.g., “My teachers want me to be quiet while waiting.”)

- Directive Sentences – Suggest what the student can do. (e.g., “When I feel like talking, I could ask my teacher for a toy to hold or just talk to her.”)

- Control Sentences – Help the student remember strategies. These can sometimes be written by the student.

- Cooperative Sentences – Explain how others can help. (e.g., “If I need help waiting, my teacher can remind me to take deep breaths.”)

Carol Gray recommends using two to five descriptive, perspective, or affirmative sentences for every one directive sentence. This helps keep the story supportive and informative rather than just a list of rules.

What Does the Research Say About Social Stories?

Social stories have been used for decades, but research on their effectiveness is more recent.

Studies have found that social stories can be used for:

- Increasing social skills

- Introducing new situations

- Reducing challenging behaviors

- Teaching functional skills and choice-making

The AFIRM modules and the National Autism Center have both recognized social stories as an evidence-based practice for students with autism.

However, not all research has found social stories to be consistently effective.

A review by Test et al. (2011) found:

- 6 studies showed social stories were effective or very effective.

- 12 studies showed they were ineffective in making meaningful changes.

A 2018 meta-analysis by Qi et al. of 22 studies found:

- 7 studies showed strong evidence that social stories worked.

- 4 studies showed that students maintained the skill even after the intervention ended.

- Social stories were more effective for reducing challenging behaviors than for increasing social communication.

A review of 41 single-subject studies, Leaf et al. (2015) found:

- 3 studies showed strong evidence that social stories worked.

- 17 studies showed partial effectiveness.

- 21 studies did not have convincing evidence of effectiveness.

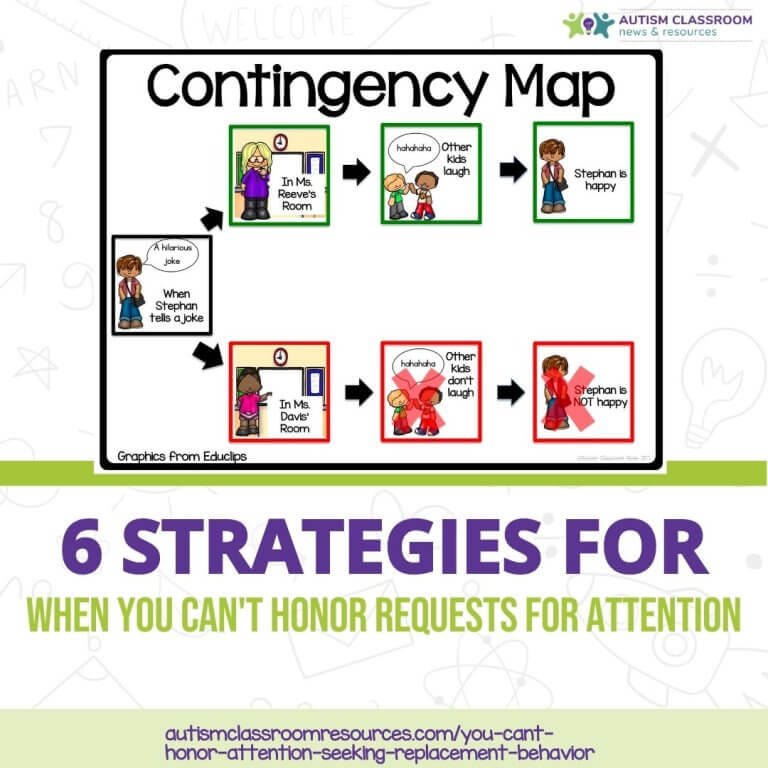

One challenge with social story research is that they are rarely used alone. In real-world settings, teachers and therapists often pair them with visual supports, reinforcement systems, and other interventions. This makes it difficult to measure exactly how much impact the social story itself has.

Do Social Stories Work for Every Student?

The answer is no.

Some students respond very well to social stories, while others show little to no change.

For example, I worked with one student who loved social stories. Any time a new issue came up, I could write a social story on the whiteboard, and he would immediately engage with it. We would later put it on paper so he could review it, and it really helped him understand expectations.

For him, social stories made a huge difference.

But for other students, they didn’t seem to have much impact.

Because of this, social stories are best used as part of a larger strategy, rather than the only intervention.

Social Stories Are an Antecedent Strategy

Most experts classify social narratives as an antecedent strategy—meaning they help prevent behavior challenges before they happen.

A well-written social story:

✔️ Prepares a student for a new or difficult situation.

✔️ Helps them understand expectations.

✔️ Gives them tools to handle challenges.

But social stories work best when paired with other supports. For example, in the earlier waiting quietly story, the student also had a token system as a reinforcement strategy. And that’s why most of my social narratives in my store, like the Anxiety Toolkit, include significant visual supports and strategies in addition to the social stories themselves.

If we could just tell students what to do and expect them to follow through, we wouldn’t need social stories in the first place. Instead, they are one piece of the puzzle in helping students succeed.

Social Stories Based on Research

-

Sale!

Self-Regulation Support Bundle: Social Stories & Visual Tools for Behavior and Emotions

$18.00Original price was: $18.00.$14.20Current price is: $14.20. Add to cart -

Calm Down Corner Tools: Social Stories & Visuals for Self-Regulation & Behavior

$5.50 Add to cart -

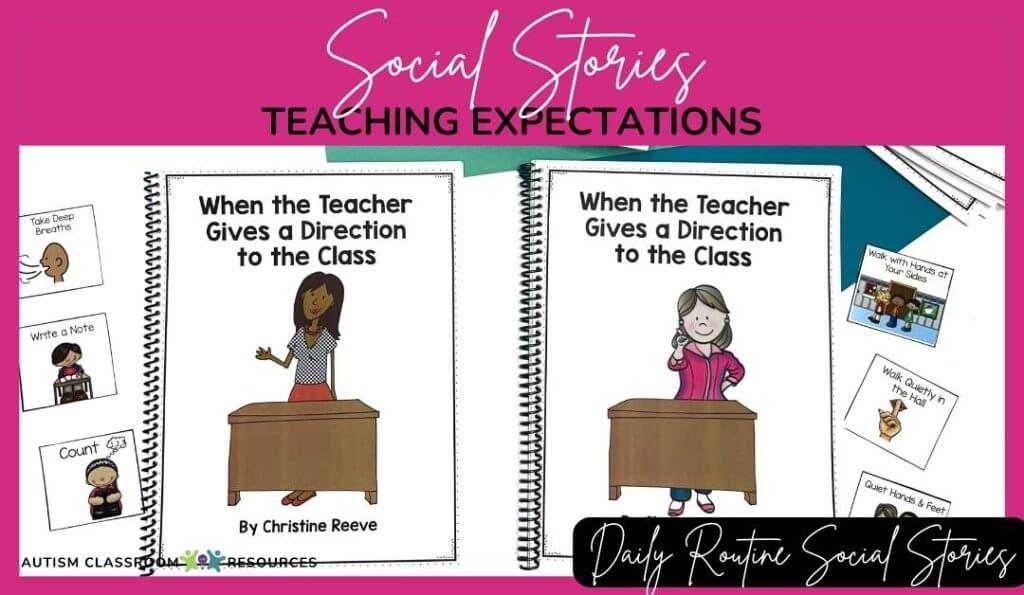

Social Stories on Following Directions and Daily Routines – Behavioral Toolkit for Students With Autism

$4.00 Add to cart -

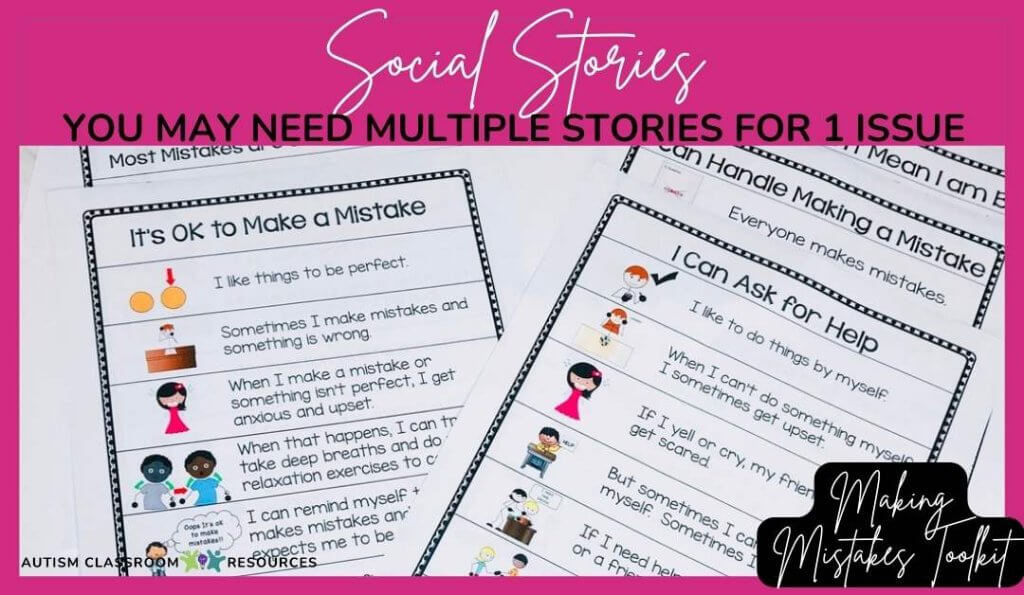

Making Mistakes Social Stories and Toolkit for Behavioral Self-Regulation

$8.00 Add to cart -

Managing Anxiety with Coping Skills, Social Stories, & Visuals Supports for Self-Regulation

$4.50 Add to cart

Free Social Story Resources

Want to try social stories in your classroom? Check out the “Who’s in Charge Here?” social story in our Free Resource Library